Options Backdating Notes from Around the Web

SEC Options Backdating Investigations List: Directorship.com has posted on its website a hotlinked list of companies ( here) that have been contacted by the SEC, revealed a probe by the SEC, or have been subpoenaed by a U.S. attorney, in connection with the options timing investigations. The Wall Street Journal’s Options Scorecard list of companies involved in the options backdating investigation ( here) is more complete, in that the Journal’s list also includes companies that have announced their own internal investigations. But the Directorship.com list zeroes in on the companies that have SEC or U.S. Attorney’s office inquiries and investigations, and is hotlinked to provide information about the authorities’ investigations. The D & O Diary is also maintaining a list ( here) of companies that have been sued in civil lawsuits involving options timing issues. The D & O Diary’s list was most recently updated on August 31, 2006, to include the new shareholders’ derivative lawsuit that has been filed against Family Dollar( here). The addition of the Family Dollar lawsuit brings the number of companies sued in shareholders’ derivative lawsuits (of which The D & O Diary is aware) to 60. The number of companies sued in securities class action lawsuits currently stands at 15. Why so Many Options Backdating Derivative Suits? The D & O Diary has previously speculated ( here) that the reason so few of the companies involved with the options backdating investigation have been sued in securities fraud class action is that for many of the companies, their announcement of options timing issues was not accompanied by the kind of stock price drop that would support a securities fraud lawsuit. But that still doesn’t explain why plaintiffs’ lawyers are so interested in filing shareholders derivative lawsuits, especially because the cases usually settle with the companies agreeing to a few corporate therapeutics and the payment of modest plaintiffs’ attorneys’ fees. An August 31, 2006 article in the International Herald Tribune entitled "In the Hunt for Heftier Awards, Lawyers Seek Backdating Suits," ( here) takes a look at the reasons why plaintiffs’ lawyers might be more interested in the derivative suits, even though the payday for the plaintiffs’ lawyers would probably be lower in a derivative suit than a securities fraud class action lawsuit. The article quotes Columbia University Professor John Coffee that "You can often bribe the plaintiffs attorney with a non-pecuniary settlement coupled with high attorney fees." The article also reports that the amount of derivative settlements has increased in recent months. Full disclosure: I was interviewed in connection with the article. Welcome: The D & O Diary extends a hearty welcome to a great new weblog that Directorship.com has launched, the Corporate Governance News blog ( here). The CGN has numerous posts throughout the day with items from around the web relating to corporate governance issues. Even though CGN has only been live a short time, The D & O Diary has already found it an indispensable resource for keeping track of governance related news and information. The D & O Diary also notes that Janice Brand, who runs the CGN blog, has a really cool title : Online Editor-in-Chief. However, the D & O Diary is still holding out for a preferred title: The Big Kahuna.

Hedge Fund Hardball and D & O Risk

In a prior post ( here), The D & O Diary commented on "Private Money and D & O Risk," noting the heightened potential for disputes to arise when the new "power players" (private equity funds, hedge funds, and buyout firms) have interests that conflict with those of management, other investors or creditors. An August 29, 2006 article in The Wall Street Journal ( here, registration required) entitled "Hedge Funds Play Hardball with Firms Filing Late Financials" presents a particularly vivid example of the problems these conflicts of interest can create. The article discusses the "new game of hardball" that hedge funds are playing with the companies in which they invest when the companies fail to file quarterly reports on time; the hedge funds are demanding immediate payment of debt or extracting substantial fees. This problem has been exacerbated recently as numerous companies have delayed filings as they deal with the accounting issues arising from options backdating problems. The Journal reports that of the 138 companies with market capitalizations over $75 that filed late second quarter financial reports, 48 companies blames options investigations. (The number of companies filing late apparently is a record, according to other news reports.) In the past, bondholders would work with company management facing delayed reporting issues to let them work out their problems. This past forbearance was in part a result of a tacit agreement between bond investors that they would not force a problem that could trigger an acceleration of all of the company’s debt, potentially forcing the company into bankruptcy. Hedge fund investors, aiming to produce outsized returns for their investors if they can force a company to redeem its bonds (which the hedge funds purchased at a discount) at their face value. In the last 18 months, at least 25 companies have had their bonds accelerated this way or were forced to pay multimillion dollar fees to bondholders. In at least one case cited in the article, this kind of dispute has led to litigation. The article reports that a trustee representing BearingPoint bondholders filed an a lawsuit against the company claiming that it was in default on two bond issues because it missed an SEC filing deadline due to accounting issues. BearingPoint's 8-K describing the litigation can be found here. While the BearingPoint lawsuit was filed against the company itself, the threat of litigation surrounding these issues, as well as the larger threat of bankruptcy looming in the background, underscore the potential D & O risk these circumstances present. The conflicting interests between a company and its investors creates an environment where accusations of wrongdoing can more easily arise. An August 30, 2006 post on CFO.com entitled "Backdating Sparks Bond Battle," ( here) provides a detailed description of the actions that UnitedHealth Group's bondholders have taken, and the company's response, based upon the company's delayed second quarter SEC filing. Delaware Court Rejects "Deepening Insolvency" Tort: The threat of bankruptcy arising from debt acceleration includes the threat of claims against the bankrupt companies' directors and officers. One bankruptcy related claim that has gained some currency in recent years is the allegation that the Ds & Os acted improperly while the company was in the "zone of insolvency" or that they were responsible for "deepening insolvency." While there is a body of case law supporting claims based on this legal theory, an August 10, 2006 decision ( here) by Delaware Court of Chancery Vice Chancellor Leo Strine rejected deepening insolvency as an independent cause of action. Chancellor Strine stated that adoption of the this legal theory would "fundamentally transform Delaware law" by imposing liability on a board of directors who, "acting with due diligence and good faith, pursue business strategy that it believes will increase the corporation’s value, but that also involves the incurrence of additional debt." Rather, the board’s conduct should be evaluated based on "the traditional fiduciary duty rule," under which the fact of insolvency is a contextual consideration to be taken into account when evaluating the board’s conduct. The board would also be entitled to the protection of the business judgment rule. Special thanks to alert reader Robert Benjamin for the link to the Court of Chancery decision. William Smith and David Topol of the Wiley Rein law firm have written a good brief summary of the Court of Chancery opinion, here. Francis G. X. Pileggi has an interesting post ( here) on his Delaware Corporate and Commercial Law blog rounding up the commentary in the blogosphere about the decision. The August 2006 issue of CFO Magazine has an interesting article entitled "Delaware Rules," ( here) discussing the role of the Delaware Court of Chancery in the evolving world of corporate governance. The article has interesting background about the Court, the chancellors, the important decisions that have become before the Court in the past, and the issues that will likely come before the Court in the future. Lawyers, Boards and Options: Law.com has an August 30, 2006 post ( here) entitled "Sonsini on Boards of Several Companies With Dubious Stock Awards." The article delivers less than the title implies, but it is still interesting. Thanks to Adam Savett of the Lies, Damn Lies blog for the Law.com link (and for the link to the article on the Delaware Corporate and Commercial Litigation blog). Chart of the Day: A scary look at what has happened to home values over the last few years, here. This looks a lot like the "before" view of the NASDAQ composite index chart ( here), circa March 2000. If the "after" version of the home values chart has as steep a decline as the incline, we could be in for a very rough ride. A brief, interesting discussion of how a housing slump could affect the economy can be found here.

SOX Consequences: Another Look?

In a prior post ( here), The D & O Diary fretted that Sarbanes-Oxley compliance costs could be driving foreign companies away from U.S. exchanges or encouraging existing public companies to delist their shares. An August 21, 2006 op-ed piece in the Wall Street Journal written by Maurice Greenberg and entitled “Regulation, Yes. Strangulation, No.” ( here, subscription required) made similar points. But two articles in the August 28, 2006 Wall Street Journal suggest that perhaps these concerns could be overstated and that there are reasons to interpret the situation more positively. First, in an article ( here, subscription required) entitled “Foreign Companies Cash in on U.S. Exchanges,” the Journal reports that 2006 YTD, non-U.S. companies have sold $5.8 billion in stock through U.S.-listed IPOs, which is already the highest annual total since 2000, and double the amount of money raised by non-U.S. companies at this point last year. Larger non-U.S. IPOs may be going to other markets, but that is not to say that deals are not getting done in the U.S. Second, in an August 28 op-ed piece ( here, subscription required) entitled “Good Governance is Good Business,” Neeraj Bhargava, the CEO of WNS (Holdings) Limited , a company that recently listed ADRs on the NYSE, lays out the reasons why his company chose a U.S. exchange listing notwithstanding the burdens of SOX compliance. Among other things, he feels that his company’s ability to clear the high regulatory burdens gives his company credibility and global visibility. He also says that as a result of greater visibility and transparency for companies traded on U.S. exchanges, his company enjoys a higher valuation and its shareholders enjoy greater liquidity for their shares. Bhargava states that he also believes that satisfying the regulatory requirements, while undeniably costly and burdensome, affords numerous benefits including “lower cost of capital, smoother follow-on financing and greater flexibility in future M & A activities.” As a result, “the benefits continue to outweigh the challenges and to drive companies toward greater efficiencies, stability and long-term growth.” So while there may well be evidence to suggest that companies are selecting away from the U.S. exchanges (as reported in the prior post), there may also be reason to conclude that there are still companies that will see the benefit of listing on U.S. exchanges. The Governance News Watch has a post ( here) on Bhargava's op-ed piece. (The Governance News Watch is an excellent online resource with daily posts on corporate govenance news.) Lawyer/Directors on Boards with Options Issues: Law.com has an August 28, 2006 post ( here) entitled “Prominent Corporate Lawyers Didn’t Stop Shady Options Deals,” in which it reports on its analysis of options practices at 17 Silicon Valley firms that had Valley lawyers on their boards. The article reports that it found “questionable grant dates” at five companies (out of the 17 studied), none of which previously has been associated with backdating questions. Each of the five has a prominent Valley lawyer on its board: Amylin Pharmaceuticals, James Gaither (Cooley Godward); Heartport, Robert Gunderson (Gunderson Dettmer); LSI Logic, Larry Sonsini (Wilson Sonsini); Lattice Semiconductor, Larry Sonsini; Echelon, Larry Sonsini. The article states that “the awards may also spur new questions about the multiple roles these directors played at a host of Valley startups now under the close scrutiny of regulators, prosecutors and plaintiffs lawyers.” A WSJ.com law blog post commenting on the Law.com article can be found here.

PIPEs Financing and D & O Risk

A casual reader of the New York Times business page or the Wall Street Journal might well get the impression that PIPEs (private investments in public equity) financing transactions are the devil’s own handiwork. Both publications have recently run stories fraught with dire tones and ominous insinuantions about PIPEs transactions. The New York Times August 13, 2006 article ( here, registration required) entitled “Secrets in the Pipeline” is a particularly egregious example. The D & O Diary is concerned that this perspective on a type of financing that is becoming increasingly popular could lead to the inaccurate and unwarranted perception that companies involved in PIPEs financings all belong in a particularly suspect risk class. While there are PIPEs transaction characteristics that could well suggest larger problems, there is nothing inherent about a PIPEs financing transaction that should cause a company resorting to this type of financing to be viewed with suspicion. PIPEs transactions typically are structured as a minority investment in a publicly traded company. PIPEs offer accredited investors the opportunity to acquire company securities at a discount to the securities’ market value. The issuer undertakes to register the PIPEs securities with the SEC, usually within 90 to 120 days of the transaction closing. There are two main types of PIPEs, traditional and structured. In a traditional PIPE, the company issues common or preferred stock at a set price. In a structured PIPE, the company issues debt securities that are convertible into common or preferred shares according to a conversion ratio that may vary. PIPEs are an established part of the financial landscape. In 2005, there were a total of 1,301 PIPEs transactions, worth $20 billion. As of August 2006, there have already been nearly 800 PIPEs transactions worth $18 billion. A PIPE transaction offers the issuing company certain advantages compared to other capital raising alternatives: • Flexibility: SEC registration is not required prior to offering or closing; • Transaction Size: To complete a secondary offering, investment bankers and investors require a minimal transaction size, roughly $ 75 mm or more. A company that needs a lesser amount, or that is simply too small to engage in a transaction of that size, has greater flexibility with a PIPEs transaction; • Efficient Use of Management’s Time: The preparation required for a PIPE is minimal compared to a secondary offering, and there is no need for management to become involved in roadshow meetings, etc. PIPEs do have downsides for the issuing company. PIPEs are dilutive of existing shareholders’ equity interest, but so too are secondary offerings. PIPEs may also attract short term investors whose interests may not align with those of management or other shareholders, as discussed below. Investors are attracted to PIPEs for a number of reasons: • Discount Pricing: Issuers offer securities as a modest discount (5% to 25%) to the market value, in light of the initial illiquid nature of the securities before the registration process is complete; • Public Market Liquidity: Once the registration process is complete, investors can sell into the public market; • Speed to Closing: Since the company is already public, extensive information is already available and there is no SEC registration process before closing. There are disadvantages for investors, primarily because a PIPE transaction usually involves only a small stake in the company. Investors do not acquire a sufficiently large stake to be able to control the company’s board or the timing or outcome of major corporate decisions. History may explain part of the reason PIPEs are often viewed with suspicion. PIPEs transactions have been known as “death spiral” or “toxic” offerings, primarily as a result of PIPEs transactions completed during 2000 and 2001, when the declining stock markets made it difficult or impossible for many companies to raise money through secondary offerings. During that period, companies conducting PIPEs by issuing convertible preferred securities where the conversion ratio changed based on the company’s share price. Companies found that investors had every incentive to drive down the company’s share price after closing so that investors could get more company shares upon conversion. Many of these transactions ended badly for the companies involved, and indeed for investors as well. The wreckage from that era has been cleared, and structured PIPEs now represent a much smaller portion of the market, and usually incorporate mechanisms (caps, floors, etc.) to remove or minimize incentives for investors to push shares down. Another reason PIPEs may be viewed with suspicion these days is that the PIPEs investors increasingly are hedge funds. Hedge funds buying securities in a PIPE are not acquiring a controlling ownership position, so their opportunity to gain from the transaction is not dependent on a restructuring or a management change; the investors must make profits from the transaction itself. So many hedge funds will “hedge” their position by selling the company’s stock short, to ensure gains even if the company’s shares decline. This understandably may make many managers and existing shareholders uneasy because of the hedge funds’ mixed motivations. Companies can set contractual limits around the timing or amount of investors’ short selling, but that typically will come at the price of a larger discount on the securities offered in the PIPE transaction. The complicated and potentially conflicted role of the PIPE investor is clearly of concern to the SEC, and in recent months there have been several SEC enforcement proceedings focused on PIPEs investors’ activities: • In March 2006, the SEC settled with three hedge funds and their portfolio manager for alledgely engaging in “naked” short sales, whereby the shorted shares in PIPEs transactions without actually borrowing publicly traded shares to cover their short position. (Short sellers cannot cover their short position with securities acquired in the PIPE transaction because they are not publicly available shares during the pre-registration period.) One of the hedge funds also shorted the company’s shares before it was publicly known that the company sought to raise money in a PIPE transaction. A copy of the SEC’s press release on this action can be found here. • In May 2006, the SEC settled an enforcement action against a hedge fund advisor and its portfolio manager for trading in the shares of 19 companies based on information that the companies were about to announce PIPEs transactions. A copy of the SEC’s press release on this action can be found here. These and other SEC enforcement actions (which can be found here and here) generally are focused on investors’ conduct or the conduct of the broker handling the PIPE transaction, rather than the conduct of the issuing company. At least recently, the problems have not involved the issuing companies. To be sure, there are transaction attributes that can justify wariness of companies engaged in PIPEs transactions: • Reset or variable rate PIPEs: These types of transactions are still getting done, but they are clearly riskier deals. The riskiest of all are transactions that lack or have insufficient caps or floors on the conversion ratio for convertible securities, because these transactions hold the “death spiral” potential. It is unlikely that any company that has other financial options would enter a transaction of this type. • Officers or directors buying shares in a PIPE transaction: This is obviously a problem – shares are being offered at below market values in a transaction that is not public knowledge until after closing. At a minimum, it raises the possibility of self-dealing or conflicts of interest (for example, in setting the level of the discount), and it raises concerns about shareholder approvals as well. • Excessive discount: Discounts for PIPEs securities typically are modest, in the range of 5 to 25%. Discounts at a level greater than this suggest desperation or the existence of some other problem with the transaction. So the picture with respect to PIPEs can be complex. But companies engage in these transactions for important and legitimate reasons, and therefore PIPEs are likely to remain an important part of the financial landscape. Clearly, the many companies engaged in these transactions cannot be treated as suspect simply because they have resorted to PIPEs financing. A company that has completed a PIPE should not be treated as a suspect D & O risk simply because of the PIPE. As noted above, there are features that could make a PIPE transaction riskier, but in the absence of those characteristics, a PIPE transaction alone should not make the company a suspect D & O risk. A particularly good short summary on about PIPE financing can be found here. A more academic (and slighly dated) overview can be found here. A good brief examination of a single company's motivations and experience with PIPE financing can be found here. Professor Larry Ribstein also has a post ( here) on his Ideoblog that is critical of the New York Times' article about PIPE mentioned above. Options Backdating Litigation Update: The D & O Diary's list of options backdating lawsuits ( here) has been updated to add the new securities fraud lawsuit that has been filed against Apple Computer ( here) and certain of its directors and officers alleging misrepresentations and omissions in its SEC filings and proxy statements about the company's alleged stock options practices. The addition of the Apple lawsuit brings to 15 the total number of companies sued in purported class action securities fraud lawsuits alleging options timing manipulations.

Proxies, Shareholder Consent, and Options Backdating Litigation

The D & O Diary’s list of options backdating litigation ( here) has been updated to include the action ( here) filed on August 23, 2006 against Zoran Corporation and ten of its past or present directors and officers. The Zoran complaint presents an interesting variation in the options backdating litigation, because it focuses on allegedly improper or misleading solicitation of shareholder proxies and consent. The complaint alleges that between July 1998 and September 2001, senior Zoran executives were granted unlawfully backdated stock options at the expense of Zoran shareholders, in violation of GAAP and the Internal Revenue Code. The complaint alleges that the defendants’ grant of the backdated options and subsequent solicitation of shareholder proxies, consent or authorization violated the Exchange Act. The complaint is filed on behalf of a purported class of shareholders who received Zoran proxy statements between April 30, 1999 and May 1, 2006. The class period covers this longer period even though the allegedly improper grants took place between 1998 and 2001 because each of the allegedly improper grants were for a term of ten years, so the first date at which the grants expire has not yet occurred, while the Company has continued to issue proxy statements allegedly containing misleading information about the grants. Under Section 14 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and its corresponding rules, whenever shareholders must approve a compensation plan, the issuer must accurately disclose the material elements of the proposed plan. With respect to stock options, the compensation disclosure must include the grant date, the exercise price, and grant and exercise tax consequences for the issuer and the recipient. If the issue is soliciting proxies in connection with the grant of stock options having a below-market exercise price, the issuer must disclose the option exercise price and the market price on the grant date, as well as the value of the options at the market price on the grant date. If the company does not apply the proper tax treatment for below market options grants, the proxy disclosures may inaccurately reflect the tax consequences for grant and exercise. Because the difference between the grant and market prices for backdated options represents income to the recipient, the recipient must pay tax and withholding on the difference. The issuer could be liable for income and FICA tax it failed to withhold upon exercise, as well as interest and penalties. In addition, because the difference between the exercise price and the market price represents compensation, it counts toward the $1 million maximum for each executive’s compensation deductibility under Internal Revenue Code Section 162(m). If the issuer did not allow for this compensation in connection with deduction for the executive’s compensation, the issuer could owe additional taxes, interest and penalties. Even if we assume that the plaintiffs' allegations are true, the value of the remedies the Zoran plaintiffs’ seek is uncertain. The complaint seeks to void the election of directors based on the allegedly improper proxies, which seems like a perhaps principled but not very financially valuable remedy at this late date (unless you assume for the sake of discussion that shareholders are better off without any of the current directors involved with Zoran in any way). The complaint also seeks unspecified damages. Whether the plaintiffs can demonstrate damages that are not simply speculative or fraught with causation questions seems debatable, at best. Bruce Vanyo and Michael Weisman of the Katten Muchin Rosenman firm have written an interesting paper entitled “Backdating Stock Options: An Overview” ( here) that examines these proxy solicitation and income tax issues, as well as other legal issues surrounding option backdating, in much greater depth. Special thanks to Adam Savett of the Lies, Damned Lies blog for the link to the Vanyo paper. The Securities Litigation Watch blog is also maintaining a list of securities class action lawsuits relating to options backdating, which may be found here. The Fugitive: Kobi Alexander,  the former CEO of Comverse Technology and a fugitive from criminal allegations filed against him in connection with the options backdating investigation at the company, has been found in Sri Lanka, according to news reports. An intersting legal commentary on the prospects for Alexander's extradition from Sri Lanka can be found on the White Collar Crime prof blog, here. A more entertaining discussion of Alexander's choice of Sri Lanka as his hideout appears on the DealBreaker.com blog, here. The DealBreaker.com also had an earlier, amusing discussion (here) of the issues a fugitive faces in attempting to flee overseas.

Now This: While many astronomers (and bloggers) still hope for signs of intelligent life on planet Earth, signs of another sort abound (here). Caution: Viewer discretion advised, may not be appropriate for all audiences.

Companies Sound “All Clear” on Options Backdating

Earlier in the summer, it was a seemingly daily occurrence for one or more public companies to announce that they were launching internal probes of their options practices. (These announcements were accompanied, and no doubt encouraged, by numerous simultaneous announcements of SEC probes, U.S. Attorney’s subpoenas, and the like.) Now as the summer has, alas, started to wane, the wave of new investigation announcements seems to have been replaced by a growing number of companies’ announcements that they have completed their internal investigations and found no evidence of options fraud or timing manipulations. Just in the last week, Intuit, Xilink, Equinix and Redback have each announced that they have completed internal investigations without finding intentional or fraudulent misconduct. The companies also announced that they have so advised governmental authorities. Several of these companies did announce that they were taking accounting charges, without restating, because their probes had found that some options were dated earlier than the actual grant date, due to administrative or processing delays. In addition, on August 21, 2006, the Corporate Library announced ( here) the results of a study of the stock options granted over the past decade by a dozen financial institutions. The study looked at stock option awards to executives at the nation's five largest banks, and at several other financial companies that made use of options. The study found no evidence of backdating of options issued to the executives at the institutions whose options were analyzed. The AAO Weblog has an interesting August 21, 2006 post about Intuit’s announcement, including a discussion of the factors that will affect how long these kinds of internal investigations are likely to take to complete. Milberg Weiss Indictment Fall Out Continues: The WSJ Law Blog has an August 21, 2006 post reporting that four more partners have left the Milberg Weiss firm. At this rate, it may wind to be a moot point whether or not the prosecutors actually prove their allegations against the firm. In the meantime, Saxena and White, formed of attorneys from Milberg’s Boca Raton office (including Chris Jones, the author of the PSLRA Nugget blog), has surfaced with an announcement of the filing of a securities class action complaint, as discussed here in the Lies, Damned Lies blog. As The D & O Diary has previously noted ( here and here), it is hard to say what the final consequential effect of the Milberg Weiss indictment will be, but the firm’s slow dissolution and the setting up of competitor (successor) firms will each have their own impact, as will the perhaps opportunistic attraction to the securities litigation arena of plaintiffs’ firms best known for their prominence in asbestos and tobacco litigation. Freddie Mac Settles ERISA Lawsuit: Freddie Mac announced ( here) on August 21, 2006 that it had agreed to pay $4.65 million to settle a class-action lawsuit that had been brought under ERISA following the company's restatement of financial results for the years 2000 through 2002. The company had been accused of overstating its earnings, inflating the value of its shares. Some of the allegely inflated stock was held in employee retirement plans. The company announced that the settlement was fully covered by insurance.

Hedge Fund Activism, Corporate Governance, and D & O Risk

Along with the burgeoning growth of the hedge fund industry has come the increasing importance and influence of activist hedge funds. This activism has taken a variety of forms, from public pressure on portfolio companies to change business strategy, to the running of a proxy contest to gain seats on the boards of directors of portfolio companies, to litigation against present or former managers. This increase in hedge fund activism has attracted sharp criticism. Martin Lipton of the Wachtell Lipton law firm lists "attacks by activist hedge funds" as the number one key issue for directors. He has issued a series of client memos ( here, here, and here) advising companies how to prepare to fend off hedge fund attacks. He characterizes the activist hedge funds as "self-seeking, short-term speculators looking for a quick profit at the expense of the company and its long-term value." Lipton has been a vociferous advocate for greater regulatory supervision of hedge funds. A July 2006 research paper ( here) written by New York University law professor Marcel Kahan and University of Pennsylvania law professor Edward Rock, entitled "Hedge Funds in Corporate Governance and Control," takes a comprehensive look at hedge funds’ impact on corporate governance. The article is replete with specific, heavily-footnoted examples of activist hedge funds’ corporate governance activities. In general, the authors regard activist hedge funds’ role in corporate governance as positive, and one that hedge funds are favorable position to play because of their investment approach and freedom from regulatory oversight. One particularly colorful example the authors examine involves Third Point LLC’s criticism of Star Gas’s CEO Irik Sevin, to whom Third Point wrote: It is time for you to step down from your role as CEO and director so that you can do what you do best: retreat to your waterfront mansion in the Hamptons where you can play tennis and hobnob with your fellow socialites….We wonder under what theory of corporate governance does one’s mom sit on a Company board. Should you be found derelict in the performance of your executives duties, as we believe is the case, we do not believe your mom is the right person to fire you from your job.

Bowing to Third Point’s pressure, Sevin resigned one month later.

While the authors contend that hedge funds have unique incentives and advantages that better position them (compared to other institutional investors) to address corporate governance issues, they do acknowledge that activist hedge funds’ actions can raise certain concerns. First, hedge funds’ interests can diverge from those of fellow shareholders, as, for example when a hedge fund is a potential buyer of a company in which it has a stake. Second, with billions of dollars of assets, hedge funds put stress on existing corporate governance structures, as, for example, when loose hedge-fund coalitions target a shareholder vote. The authors acknowledge these concerns, but find them no worse than concerns surrounding other institutional investors, and argue that these concerns are not sufficient to justify greater hedge fund regulation.

The most serious criticism of hedge fund activism, the one Marty Lipton raised, is that hedge funds exacerbate short-termism. The authors argue that the market will enforce adaptive approaches to deal with the potential negative effects of hedge fund short-termism. The authors cite Lipton’s own "Hedge Fund Attack Response Checklist" as an example of just such an adaptive device, about which the authors state:

[Lipton’s suggestions] are terrific ideas, not just to deal with activist hedge funds but in general. If companies follow Lipton’s advice, hedge funds will have already made significant positive contributions to the management of U.S. companies. Moreover, if hedge funds can succeed despite companies taking these measures, we think chances are reasonably high that they have a good point.

The authors’ conclusion is that "market forces and adaptive devices take by companies individually in response to activism are better designed to help separate good ideas from bad ones than additional regulation."

The increasing influence of activist hedge funds has important implications for D & O risk. Specifically, activist hedge funds’ corporate governance activities can involve litigation, including litigation directed against directors and officers. A prominent recent example is Cardinal Value Equity Funds’ litigation campaign involving Hollinger International and allegations of Conrad Black’s self-dealing and other transactions, which culminated in a derivative lawsuit for breach of fiduciary duty against Hollinger’s board of directors. After an independent Board committee investigation, Cardinal negotiated a $50 million settlement with the directors not directly implicated in the self-dealing. The settlement was funded by Hollinger's D & O insurers. (Hollinger's press release may be found here. )

Hedge funds have even sought appointment as lead plaintiffs in securities fraud lawsuits. Indeed hedge funds often are the investors with the largest losses, but because they often engage in short-selling, they may be subject to unique "reliance" issues and therefore many not be "adequate" class representatives. For that reason, courts have often, though not uniformly, rejected the appointment of hedge funds as lead plaintiffs.

But because activist hedge funds view litigation as an essential part of their activist strategy, the role of hedge funds as "the prime corporate governance and control activists" has very important implications for D & O risk. While hedge funds’ activism potentially could contribute to improved corporate governance, the willingness of hedge funds to achieve their goals through litigation against directors and officers represents a dangerous variation of D & O exposure. Marty Lipton may not have been far off the mark when he described the threat of activist hedge funds as the most important issue for corporate officials.

SEC Commissioner: Potential Outside Director Liability for Options Backdating?

In an August 15, 2006 speech entitled “How to be an Effective Board Member” ( here), SEC Commissioner Roel Campos made a number of interesting comments about the potential liability of corporate board members, and for that reason the entire speech merits reading. Of particular interest to The D & O Diary are Commissioner Campos’ remarks about the options backdating cases: Finally, let me discuss briefly stock option backdating cases. So far, the SEC has brought two cases, against Brocade and Comverse, and we're likely to bring more in the future. As yet, we have charged only officers in option backdating cases. However, if the facts permit — and I want to emphasize that all of our Enforcement cases are very fact specific — it wouldn't surprise me to see charges brought against outside directors. I also think that the backdating cases can provide a few lessons in terms of "do's and don'ts" for directors. In my opinion, the two big "don'ts" are: (1) don't use "as of" dates unless you have carefully thought about the consequences and have explicit approval from legal counsel that it is acceptable to use an "as of" date; and (2) don't assign critical board functions to "committees of one," unless you're extremely careful to adopt procedures to ensure that there are appropriate checks and balances in place. In terms of "do's", let me highlight one: do pay attention to procedures and processes — such as properly signing and dating Actions by Unanimous Written Consent — because simple logistics can get you into trouble.

The D & O Diary finds a couple of points of interest in these remarks. First, the Commissioner is discrete about the possibility that outside directors might face exposure to SEC enforcement actions in connection with options backdating, saying only that he wouldn’t be surprised if it happened, but The D & O Diary reads that to mean that it probably will happen. Indeed, the Commissioner seems to overlook that “Wells notices” already have been served on three outside directors of Mercury Interactive. (A prior D & O Diary post discussing the Mercury Interactive Wells notices may be found here.) Second, the Commissioner may not have anything in particular in mind in his reference to the Committee of One, but The D & O Diary believes that this could be a reference to the situation at Brocade Communication, where Silicon Valley legal giant Larry Sonsini, who was an outside director of Brocade, for a time allegedly operated as a Brocade board compensation committee of one. A prior D & O Diary post commenting on the circumstances at Brocade may be found here. A WSJ Lawblog post commenting on Sonsini's service as a committe of one may be found here. The Commissioner’s further remarks with respect to Committees of One are interesting in light of the situation at Brocade: I think my advice to "don't assign critical decisions to committees of one" is fairly self-explanatory, but apparently it's advice that's also been ignored. Again, I'm not suggesting that committees of one are per se wrong — Delaware law permits it, after all. However, at best, it's far from being a "best practice" in good corporate governance. And at worst, it's a signal to the company's officers that directors are not taking their obligations as a director seriously and are willing to let expediency guide their decision-making.

Comment on ABA's Thompson Memo Resolution: In a prior post, The D & O Diary commented on the American Bar Association's recent resolution calling for revision of policies embodied the Thompson Memo. An August 14, 2006 post in the SEC Actions blog has the following interesting comment on the ABA's action: In view of the continued actions by the government that are eroding fundamental rights in the name of effective law enforcement, the ABA positions represent a good start, yet more is necessary. What is needed here is a recognition by the government - both DOJ and the SEC - that it cannot effectively enforce the law by eroding it. In fact, eroding fundamental rights disrespects the law. Rather, both DOJ and the SEC need to reform their standards for evaluating cooperation to focus on what they need: the basic facts involved and reasonable assurances that the questionable activity has been halted and will not reoccur. If good prosecutors are satisfied on these points they should have what they need in most cases to evaluate cooperation and make whatever prosecutorial decisions are necessary without eroding fundamental rights of the company and its employees.

The D & O Diary couldn't agree more.

Another Perspective on KPMG and the Thompson Memo

It is always rewarding to The D & O Diary when a blog post provokes a thoughtful and interesting response. The D & O Diary's August 14, 2006 post about the Thompson Memo provoked a substantial response that is sufficiently interesting that we asked for and received the author's consent to reproduce the response in its entirety, as a guest post. The D & O Diary's first-ever guest blogger is John F. McCarrick, an attorney in the New York office of the Edwards Angell Palmer & Dodge law firm, and here is his guest post: I enjoy reading your blog and wanted to comment on your post about the Thompson Memo. The reason this is of particular interest is because I have been working with several leading insurers for the past several months on a new legal expenses policy designed specifically to address this particular exposure. During the course of my research in connection with this project, here is what I concluded:

First, the employee legal expense advancement issue is not just a DOJ/Thompson Memo issue -- as would appear to be the case based on the American Bar Association and other advocacy groups' public statements about the evils of the Thompson Memo. The SEC employs similar strategies in its investigations based on the principles of the Seaboard report, and the NYAG applied this strategy in the Theodore Sihpol/Bank of America case to deny Sihpol legal expense advancement from BofA. Given the broader use of this strategy (note that the SEC initiates many more investigations each year than the DOJ does in this area), I find it interesting that no one is challenging the SEC or NYAG with the same intensity as in connection with the Thompson Memo criticisms.

One could look at the employee legal expense advancement issue as a balancing of two conflicting public policy concerns. The legitimate concern embodied in the Thompson Memo is that when a company under investigation employs a single counsel to represent its interests and those of all of its employees, such legal representation creates an opportunity for the company to improperly influence the cooperation of those of its employees being questioned in connection with the investigation. So, how can this be cured? Arguably, if the company hires separate counsel to represent its employees, the fact that the separate counsel has been retained by, and is being paid by, the company still creates an opportunity for improper influence of the employee's cooperation because the law firm and the employee recognize that the company is still paying the bills and therefore calling the strategic shots. Moreover, even if the employee goes out and hires his or her own counsel, the opportunity for improper influence remains because even though the company may no longer be calling the strategic shots, it still is paying the bills and

has some overt or subtle expectations about what it expects in terms of the employee's cooperation with the company in the investigation.

The counterweight public policy concern is that employees being questioned in connection with corporate white collar crime cases should have the benefit of competent counsel, given the personal implications involved if the government does not believe the employee is being fully truthful, regardless whether the employee has any culpability in connection with the underlying issues being investigated. Thus, even though 6th Amendment rights to counsel don't come into play until indictment, in practice, invocations of the Thompson Memo frequently occur at an early ( i.e., pre-indictment) stage of the investigation, and before an employee has a constitutional right to counsel.

With respect to your blog, I don't think it's correct to say that Judge Kaplan found portions of the Thompson Memo to be unconstitutional. To the extent there were right to counsel (post-indictment only) or due process (possibly pre- and post-indictment) violations, Judge Kaplan found that the actions of the government in furtherance of the Thompson Memo constituted unconstitutional conduct. Accordingly, I think one could reasonably argue (as the DOJ currently is arguing) that the Thompson Memo itself is not subject to challenge on constitutionality grounds, meaning that had the government acted in a less overt or threatening way in connection with a particular investigation, it nevertheless could have evaluated the company's cooperation (for indictment purposes) by looking at, among other things, whether the company was advancing legal expenses to employees.

Also, the invocation of the Thompson Memo in the KPMG case took place after the individuals were indicted. This is an important fact because there is no Sixth Amendment right to counsel prior to indictment. Thus, to the extent Judge Kaplan determined that a constitutional breach had occurred, such breach occurred with respect to the Sixth Amendment and therefore, constituted post-indictment conduct by the government. This is significant because the trigger for coverage under D&O policies (even the broader Side A DIC policies) is an indictment; meaning that if the Thompson Memo is invoked with respect to an employee pre-indictment, D&O coverage would not respond to pay for that employee's legal expenses.

Finally, D&O policies typically require that a "wrongful act" be alleged against a covered person in connection with a "claim" in order for coverage to be triggered. However, as a practical matter, invocations of the Thompson Memo occur most frequently pre-indictment (of the person or insured entity), and the government generally does not identify wrongful acts by the targeted employees when it insists that the company cease advancing legal expenses for that employee.

McCarrick is of course correct about Judge Kaplan's decision about the constitutionality of the Thompson memo; it was not the memo itself that was declared unconstitutional but the way the government had implemented it in the KPMG tax shelters case. He also makes a very good point about the policies of the SEC and the NYAG which also could have the effect of discouraging companies from funding employees' defense fees. His distinction between pre-indictment and post-indictment expenses (and constitutional rights) is important. Option Backdating Litigation List Update: The D & O Diary updated its list of options backdating litigation on August 15, 2005, to add the new securities class action lawsuit that has been filed against Witness Systems. This brings the number of options timing securities fraud lawsuits to 13. The D & O Diary notes that the Witness Systems lawsuit, and the lawsuit filed most recently prior to that one, which was filed against Broadcom, were filed by firms that are best known for work in asbestos and tobacco class action litigation -- the Witness Systems case was filed by the Motley Rice law firm, and the Broadcom case was filed by the Kahn Gauthier and Swick firm. Perhaps the Milberg Weiss firm's misfortune is attracting opportunistic competition from other segments of the plaintiffs' bar. You Tube Interlude: On the theory that anything that was the subject of a Wall Street Journal article (subscription required) is a suitable post topic for this blog, The D & O Diary offers this pop culture interlude. Readers who stay up later on Saturday nights than does The D & O Diary are probably already familiar with the "Lazy Sunday" video (also known as "The Chronicals of Narnia Rap"), mentioned in the Journal article. Here is a link for those for whom, like The D & O Diary, Saturday Night Live broadcasts occur two hours post-bedtime. The Lazy Sunday video spawned numerous spoofs. The D & O Diary's favorite spoof is the "Lazy Sunday UK" version (also known as "We Drink Tea Rap") which may be found here. Warning, turn the sound on your computer down before launching.

Thompson Memo Criticism Builds

As noted in this prior D & O Diary post, at least one U.S. District Court has found the Thompson Memo unconstitutional. At its recent annual convention, the American Bar Association adopted a Report issued by its Task Force on Attorney-Client Privilege. The Report urges the Department of Justice to withdraw or revise a number of provisions in the Thompson Memo, including in particular the provisions encouraging corporations seeking to avoid criminal prosecution to withhold the payment its employees’ criminal defense fees. Among other things, the report states that this provision of the Thompson Memo is “inconsistent with ABA principles, good corporate governance, the role of lawyers in our adversarial system of justice and individual Constitutional rights.” The Task Force presented four specific recommendations for the revision of the Thompson Memo, which may be found here. Professor Ellen Podgor, in a post on the White Collar Crime Prof blog, presents a more practical argument for the Department of Justice to revise or abandon the Thompson Memo – that is, as long as prosecutors act upon the Thompson Memo’s requirements, they run the risk that future prosecutions will be in jeopardy, as companies could escape prosecution or individuals walk free if additional courts find the prosecutors’ reliance on the Thompson Memo to be unlawful. She notes "as a taxpayer, I am not sure this benefits our pocketbooks." And in an article in the August 14, 2006 issue of the National Law Journal, two defense attorneys present their view that Judge Kaplan’s opinion in the KPMG tax shelters case was correct in declaring the Thompson Memo unconstitutional, but flawed by its failure to throw out the criminal cases against the individual defendants altogether. Their argument is that Judge Kaplan’s solomonic effort to compel KPMG to pay the individual defendants’ attorneys’ fees failed to recognize that the “government’s conduct prejudiced the defendants’ ability to make critical pretrial decisions, including what lawyer to hire; whether and on what terms the defendants’ might cooperate with the government or plea bargain; or other lawyering that might prevent an indictment.” Their argument is that denial of legal fees at the early stages “cannot be atoned for after the fact” because the “full panoply of pretrial lawyering [is] forever lost when the government interferes with the attorney-client relationship.” Options Backdating Litigation Update: The D & O Diary's options backdating litigation list, which may be found here, has been updated to add the new securities fraud class action lawsuit that has been been filed Broadcom Corp. The number of securities fraud lawsuits based on options timing allegations now stands at 12. Note: The list was updated again on August 15, 2006, to add the new securites fraud lawsuit that has been filed against Witness Systems. Calvin's Dad Explains the Universe: Calvin's Dad (of Calvin and Hobbes fame) was a patent attorney, and that is close enough to a good reason to include a link to this site containing a distillation of Calvin's father's pronouncements on the mysterious workings of the universe.

Brocade Communications Settles Shareholders' Derivative Lawsuit Concerning Options Backdating

According to August 10, 2006 press reports, Brocade Communications settled the derivative lawsuit that shareholders had filed in federal court in San Francisco in connection with Brocade's options-award timing miscues, in exchange for an agreement to adopt certain therapeutic governance measures and the payment of $525,000 in legal fees. The settlement also involves contributions to the legal fees of the defendant directors and officers (amount undisclosed). Fifteen current and former Brocade Directors and Officers reportedly participated in today's settlement (including former Brocade director and Wilson Sonsini partner Larry Sonsini.) KPMG, Brodcade's auditor, also reportedly settled. Gregory Reyes, Brocade's former CEO, who faces criminal charge in connection with options timing problems at Brocade, did not take part in the settlement. Other shareholder lawsuits, including shareholder fraud lawsuits, remain pending. A hearing on the stipulation of settlement is scheduled for August 18.

FCPA, Options Backdating, and D & O Exposure

In this prior post, the D & O Diary noted the recent resurgence of the 70’s vintage statute, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Recent developments in the Comverse Technology options timing investigation underscore the increasing importance of the FCPA, particularly as the options backdating scandal continues to unfold. On August 9, 2006, the SEC filed a civil enforcement complaint against three former officers of Comverse Technology. (The Affidavit filed in conjunction with the criminal complaint filed against the three individuals can be found here, even though the document says on its face that it is to be filed under seal.) The SEC Complaint alleges “a fraudulent scheme” by the three defendants “to grant undisclosed, in-the-money options to themselves and others by backdating stock option grants from 1991 through 2001 to coincide with historically low closing prices for the Company’s stock.” The SEC Complaint alleges a variety of securities laws violations, including specifically violations of the books and records provisions of the FCPA, which are codified as amendments to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. The FCPA allegations are that the defendants “knowingly violated …internal controls” and “falsified books, records or accounts.” These same kinds of allegations are likely to be a recurring part of future enforcement actions arising out of the options backdating investigations. Indeed, according to press reports, the criminal indictment entered on August 10, 2006 against former officials of Brocade Communications also contained "books and records" allegations. The D & O Diary's prior post about the FCPA noted that one of the dangers from an FCPA enforcement proceeding is the possibility of follow-on litigation. A recent securities fraud lawsuit settlement provides a glimpse of the way FCPA violations can spawn follow-on litigation, including specifically follow-on securities fraud lawsuits. On August 9, 2006, Willbros Group, Inc. announced that it had settled the 2005 class action lawsuit that had been filed against the Company and several of its directors and officers. The Complaint alleged that the company had been the subject of numerous of numerous investigations “because the Company engaged in a campaign of illegal and illicit bribery of foreign government officials in Bolivia, Nigeria and Ecuador to successfully obtain construction projects.” The Complaint alleged that the company was forced to restate several years of financial statements and to establish a reserve to accrue for possible fines and penalties for FCPA violations. The Complaint alleged that as a result of these violations, the Company had misrepresented its true financial condition. The Complaint alleged that the company’s share price declined 31% when these matters were disclosed. In its August 9 press release, the Company did not disclose the amount of the securities class action settlement, but the press release did state that the amount of the settlement would be funded by the company’s insurance carrier. The Willbros settlement illustrates the growing D & O risk that increased FCPA enforcement activity could represent. The threat is not so much from the underlying FCPA enforcement action itself; any FCPA fines and penalties likely would not be covered under most D & O policies. Rather, the threat is from the potential liability that could arise in any follow-on civil action, including any follow-on securities fraud lawsuit like the one filed against Willbros Group. Any settlement or judgments incurred in a follow-on action, as well as defense expenses, would usually be covered under the typical D & O policy. As FCPA enforcement actions grow in number and magnitude, this exposure could pose an increasingly greater D & O risk. An August 10, 2006 CFO.com article discussing the Willbros settlement, as well as the simultaneous resignation of the company’s CFO (who had been a defendant in the securities fraud action), may be found here. Two particularly interesting articles discussing the Comverse Technology criminal complaint may be found at the White Collar Crime Prof blog, and at the Securities Litigation Watch blog. A particularly provocative contrarian view of the Comverse Technology criminal complaint and of the whole options backdating morass may be found on this post on Professor Ribstein's Ideoblog. Big Numbers: An August 10, 2006 post on Bloomberg.com reports that The number of companies with stock options grants under scrutiny passed 100...At least 105 companies have disclosed internal or federal probes, according to data compiled by Bloomberg News. Nineteen people have lost their jobs, five face criminal charges and one of them -- Comverse Inc. founder Jacob Alexander -- didn't show up for his arraignment yesterday. A separate article on Bloomberg.com, also dated August 10, reports that: UnitedHealth Group Inc. Chairman William McGuire sparked outrage among some stockholders over his $1.8 billion in potential stock-option gains. Turns out, the board of directors that granted those options got a share of the wealth, too. UnitedHealth's 10 non-executive directors held $230 million in stock as of March 21, according to the health insurer's most recent proxy...``You have to ask yourself, are these people paying attention to the mission of the corporation, or are they being distracted by the amount they're getting themselves?'' says Minnesota Attorney General Mike Hatch, who is investigating Minnetonka-based UnitedHealth along with federal authorities...A board committee is reviewing 45,000 separate option grants made to 15,000 people over 13 years, the company said in a statement. And a Japanese man was arrested this week after making 37,760 silent calls to directory inquiries because he wanted to listen to the "kind" voices of female telephone operators, according to news reports. Sudden Complications: United Airlines' aviation war risk insurance is up for renewal on August 31, 2006. Read the story here. Yet Another Globalization Downside: The U.S. economy is trading factory workers for real estate agents. Take a look at this uncanny chart here.

Catching Up on Options Backdating

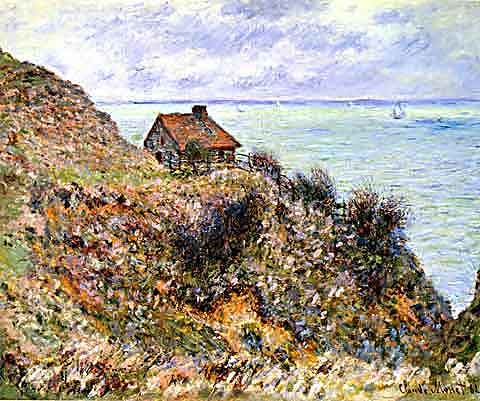

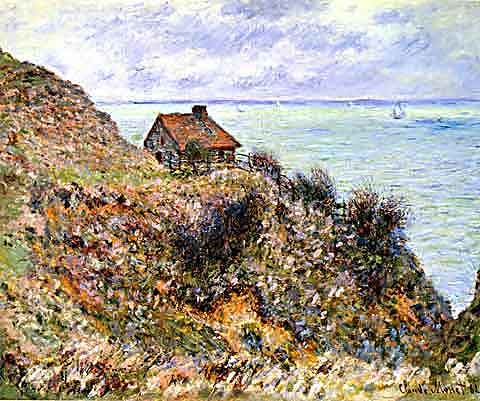

Molex Execs Repay Pay: In one of the more interesting (and speediest) resolutions by a company of options timing concerns, 12 executives of Molex, Inc. agreed to repay the company a total of $685,000 to cover gains they realized on misdated options. The executives also agreed to have the prices raised on their unexercised options, reducing the options’ value and ensuring that the executives would not benefit in the future from the misdating. The Company’s press release states that the misdating was due to clerical error that in some instances had the effect of diminishing the value of certain options awards to the executives. The August 3, 2006 Wall Street Journal article describing the company's action points out that no other company involved in the options backdating investigations has ordered a repayment from the executives who profited. The D & O Diary notes that D & O insurers would likely contend that the Molex executives’ payments, which represent a return to the company of compensation overpayment, would not be covered under the typical D & O policy, because it would not constitute covered "loss." Interestingly, the "personal profit" exclusion typically found in most D & O policies would not appear to preclude coverage for the payments even if the payments were otherwise covered "loss," because the payments were not made pursuant to an "adjudication" that the executives were not legally entitled to the excess payments. (To be sure, many policies allow insurers to trigger the exclusion by obtaining a judicial declaration that amounts paid represented "remuneration" to which insured persons were not legally entitled.) Hat Tip to Adam Savett of the Lies, Damned Lies blog for the Molex link. Yet Another Variant of Options Timing Manipulations? As The D & O Diary has noted in prior posts, the current options timing scandal encompasses several different types of options timing practices: options backdating, which involves the retroactive setting of the grant date to an earlier date when the company’s share price was lower; options springloading, where the grant date is set ahead of the release of positive news expected to raise the company’s share price: and hiring-related options grants, which can involve setting options award dates at a time prior to an employee’s hiring, or simply at a false hiring date, to increase the value of the new hires’ options. A July 20, 2006 article in The Economist (subscription required) identifies yet another variant of options timing: "bullet-dodging," which involves delaying an option grant until after the bad news is announced. The value of an award made prior to the bad news announcement would diminish if shares declined in reaction to the news; waiting until after the bad news to make the award averts the decline and increases the award recipients profits if the company’s share price later rebounds. The D & O Diary believes that it is important to distinguish these distinct options practices, as each involves different sets of issues and its own sets of concerns. For example, the profits for backdated options are locked in; profits from springloading or bullet dodging are far less certain. By the same token, hiring-related options practices lack the element of self-dealing that may characterize the other options timing practices. These differences are significant and potentially could substantially affect investigative outcomes, as well as the resolution of any civil litigation based on allegations of options timing manipulations. One further note about hiring-related stock options: the August 9, 2006 criminal complaint is entered against three former Comverse Technology officials alleges an interesting variant of the hiring-related options timing manipulations. The complaint alleges that the defendants created a slush fund of backdated options granted to fictitious employees and later used these options to recruit and retain key personnel. One of the ficticious names allegedly used was "I.M. Fanton." Options Investigations and Company Share Prices: Notwithstanding the media barrage surrounding the options backdating scandal, relatively few of the companies involved in the various investigations have been sued in securities fraud lawsuits – to date, only 11 companies. ( The D & O Diary is tracking Options Backdating related litigation here.) One possible reason why the plaintiffs’ bar may be shying away from suing more companies is the lack of share price decline for companies involved in the investigations. An August 7, 2006 Forbes article reports its analysis of stock prices of 65 firms that announced financial restatement or government investigations related to their options-granting practices. Though some companies saw dramatic share price declines, the group as a whole saw no abnormal drop compared to the wider market. The companies’ share prices fell an average of 7.4% since the announcements (most of which have taken place in the last three months) compared to a 9.4% decline in the NASDAQ Composite Index since May 1. The article does note important difference; for example, companies that have lost senior executives have suffered more than others. The companies with the most significant price declines are listed here.The absence of significant share price declines for most of the companies involved in the scandal supports The D & O Diary’s view that the scandal will not be a "severity event" for the D & O insurance industry. Hat tip to the Vangal blog for the Forbes link. Cooperman Paintings: For those D & O Diary readers who were interested in my prior post about the Cooperman Paintings heist and its impact on the Milberg Weiss indictment, you may want to visit the post again. I have added images of the paintings.

Private Money and D & O Risk

The Wall Street Journal’s recent series on "Private Money" describes the "new financial order" arising from "the new rules of private equity game." According to the July 25, 2006 Journal article (subscription required) entitled "Cash Machine: In Today’s Buyouts, Payday is Never Far Away," the new power players are private financiers – hedge funds, buyout firms and venture capital firms highly skilled at quickly extracting cash from the firms they acquire. The private financiers collect dividends, fees for advising, and fees for stock underwriting and management. The magnitude of the cash hauled out can be stunning; the article describes the $22 million in professional fees and $448 million in dividends that the private investors pulled out of Burger King prior to its May 2006 IPO. The article describes the sequence of events involving Dade Behring, Inc, a medical diagnosis company that found itself saddled with enormous debt that was incurred to buy out private investors’ equity stake. Eventually the debt burden drove the company to the brink of bankruptcy. Creditors formed a committee to examine the conduct of Dade Behring’s "owners, directors and advisors." The creditors considered bringing claims relating to "illegal dividends, illegal stock redemptions and impairment of capital." (The company later recovered and subsequently went public.) Although the Dade Behring creditors ultimately did not bring a claim, the example provides a cautionary tale for those who must assess the potential risk of D & O claims arising under the new rules of the private equity game. The presence on company boards of representatives of the new power players whose interests may conflict with the interests of the company, other investors, or creditors, creates an environment where accusations of wrongdoing may more easily arise. These same risks are present even if the private equity investors do not have company representation; the board’s actions for the benefit of private equity investors could draw criticism of the board even if the investors do not have board representation. This risk could be particularly applicable where a debt-saddled company is driven into bankruptcy. Creditors may claim they are owed special duties while the company was in the "zone of insolvency." These claimants may assert that the private investors extraction of dividends, management fees, or equity buy-outs, represent a form of "looting" or "waste" or a violation of other legal duties, and that the other directors violated their duty of care for permitting these actions. While the significance of private funding in the world of corporate finance has long been recognized, the Wall Street Journal series reflects a growing realization that the increasing influence of private funding has its consequences. Among those consequences is a potentially growing possibility of conflicting interests that could trigger D & O claims. Crafting the appropriate insurance response when these risks are present requires a skilled hand. The presence of differing potential interests, and differing insurable interests, creates problems of program structure and of content. In terms of policy wordings, the formulation of the Insured versus Insured exclusion present particular potential concern. Policy definitions, particularly the definition of "Loss," as well as the conduct exclusions, also could be particularly important, as would common endorsements such as a Major Shareholder exclusion. Zone of Insolvency: Stephen Bainbridge, UCLA Law Professor and author of the ProfessorBainbridge.com blog, has written an interesting paper examining (and questioning) the duties of directors of companies that are in the "zone of insolvency." The paper may be found here. The One Sin Greater Than Plague or Death: In our time, we are comfortable thinking about issues such as debt or bankruptcy as strictly practical or legal concerns. But in an earlier times, debt was a moral issue. This is starkly illustrated in Henry Knighton's contemporaneous account of the Black Death in England; Knighton reports that "the Bishop of London sent word throughout his whole diocese giving general power to each and every priest...to hear confessions and to give absolution to all persons with full episcopal authority, except only in case of debt. In this case, the debtor was to pay the debt, if he was able while he lived, or others were to fulfill his obligations from his property after his death." Knighton's report appears in Eyewitness to History, a fascinating 1988 compilation of first-hand accounts of historical events, edited by John Carey.

SOX Consequences: London Is Calling and Companies Are “Going Dark”

As detailed in this prior D & O Diary post, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act has imposed enormous compliance burdens and expense on companies whose shares are traded on the U.S. securities exchanges. It is hardly surprising that, according to an August 8, 2006 Wall Street Journal article (subscription required), U.S. exchanges have lost ground in luring foreign listings. The article states that “[n]ine of the world’s ten largest non-U.S. IPOs listed in New York in 2000; last year, 24 of the largest 25 chose other markets, with London the leading alternative.” Sources cited in the article suggest that the U.S. regulatory burden is the principal reason for the shift, but that high U.S. underwriting fees (which may be as much as double as those assessed in London) may be a contributing factor. The aversion to the U.S. exchanges is not limited to non-U.S companies, nor is it limited to companies contemplating their public debut. According to an August 3, 2006 New Jersey Law Journal article entitled “Companies ‘Go Dark’ to Avoid SOX Compliance,” the high cost and burden of Sarbanes-Oxley compliance “appear to be driving of companies to simply withdraw from the major exchanges.” Some companies are going private, and others are “going dark” by deregistering their stock with the SEC. Shares of companies that go dark are listed on the “ Pink Sheets,” an electronic quotation medium for companies not listed on stock exchanges. Public companies can generally file for deregistration if they have fewer than 300 shareholders of record or fewer than 500 holders and less than $10 million in assets in each of the prior three years. Even companies with thousands of shareholders can meet these requirements if investors have their shares in “street name” (where a customer’s securities are held in the name of a brokerage firm instead of the individual’s name, in effect representing a single shareholder of record). Other companies “go private,” that is, restructure to concentrate ownership in the hands of management or private equity investors, after which their shares are not traded publicly, even on the OTC markets. According to an academic study cited in the article, and about which more below, in 2002, when SOX was enacted, 65 publicly traded companies “went dark” and 61 went private. In 2003, 183 companies “went dark” and 79 went private. In 2004, the most recent year studied, 122 companies “went dark” and 66 went private. The academic study referenced in the article is the recent paper written by Professors Christian Leuz, Alexander Triantis, and Tracy Wang, entitled, “Why Firms Go Dark? Causes and Economic Consequences of Voluntary SEC Deregistrations.” The study may be found here. The study examines companies that “went dark” or and companies that went private both before and after the enactment of Sarbanes Oxley, to determine the causes and consequences of the companies’ actions. The authors found that in companies’ press releases announcing the companies’ decision to go dark, the usual reason stated is the high cost of SEC reporting and SOX compliance. The authors found the most likely companies to go dark are smaller firms with relatively poor performance and low growth, for whom reporting burdens are particularly burdensome. For many firms, the decision to go dark is a response to financial difficulties and deteriorating growth opportunities. By contrast, companies that go private are typically larger, better performing and less-distressed then going-dark firms. Interestingly, while the number of going-dark firms has “surged” following the enactment of Sarbanes-Oxley, the incidence of going-private transactions has not increased. While Sarbanes-Oxley may have been an unavoidable reaction to the enormous corporate frauds that led to its enactment, it is clearly diminishing the number of companies that seek to be listed on U. S. exchanges. This unintended consequence is not only affecting the way business is conducted in this country but is also affecting the global economy as well, in ways that do not improve this country's economic competitiveness. Police Power and Its Limitations: I expect that many police personnel, sitting around the station house bragging about the day they "apprehended the perpetrator," occasionally allow themselves to fantisize that some day they too might get a call, like the one that came in to Kennewick, Washington police on August 4, 2006, to run down a stolen truck full of doughnuts. Miraculously, when the perpetrator was finally apprehended, the "entire load of glazed, sugar and cream doughnuts, as well as apple fritters and bear claws" was intact. A more complicated call came in to police in Aachen, Germany on August 2, 2006, when a woman called to complain that her husband was not, shall we say, fulfilling his marital duties. Because the police confessed themselves unable to resolve the dispute, let alone issue any kind of official order, the 44-year old woman was frustrated both by her husband and by the entire police force in a single evening. On the other hand, the British police should be relieved that this sort of thing falls outside police jursidiction, as, at least according to at least one report, seven million British Women are unhappy with their sex lives. That's a heck of a lot of non-perpetrators. The D & O Diary wonders if the problem has something to do with cream doughnuts.

More Notes About the Milberg Weiss Indictment and the Declining Number of Securities Lawsuits