Options Backdating: Act Two?

One of the standard features of most articles discussing the options backdating scandal has been the obligatory statement that backdating largely disappeared after the 2002 passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, as a result of the Act’s requirement (in Section 403(a)(2)) that all transactions in the company’s shares involving directors or officers must be documented to the SEC "before the end of the second business day following the day" on which the transaction took place. But a new report entitled "The Backdating Scandal’s Second Act?," shareholder advisory firm Glass Lewis raises doubt about whether Sarbanes-Oxley eliminated the practice after all, and suggests that there may be a whole new round of options timing revelations ahead. According to news reports ( here and here), Glass Lewis found that many companies have not been complying with the timing requirements for filing options related paperwork on SEC Form 4. The report found that the SEC rarely cracks down on companies for filing their paperwork late, which allows the opportunity to change the actual date the stock options were granted to a day when the stock was trading at a lower price. The firm reviewed hundreds of thousands of Form 4 filings from January 2004 to June 2006 and pinpointed some 6,000 questionably timed stock-options grants that were dislosed late to investors. Glass Lewis found that in several instances the price of company shares increased materially between the purported grant date and the date of the filing. One of the companies Glass Lewis identified in the report is Silicon Image. According to news reports ( here), Glass Lewis found that several Silicon Image officers were late filing Form 4s in connection with options grants during 2004, 2005 and 2006. In 11 out of 12 grants during that period, Silicon Image’s stock price increased between the grant date and the (late) filing date. According to an October 31, 2006 San Jose Mercury News article ( here), Silicon Image has launched an internal review of its option practices. The Glass Lewis Report cited eight other companies whose Form 4 filings showed a similar jump in share price between the grant date and the filing date. Based on this analysis, Glass Lewis questioned whether the options timing scandal might be about to enter a "second act," involving potentially "hundreds" of companies that may have backdated options grants even after the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley reforms. The report also notes that even where the company’s Form 4 filing were unintentionally or inadvertently filed late, the company’s regulatory filing practices still raise concerns about the company’s internal controls. It is too early to tell whether or not the Glass Lewis "second act" analysis really does portend a significant new phase in the options timing scandal. It is worth noting that the original trigger for the initial round of options backdating investigations was a similar academic analysis of options practices. And even though there are as yet no claims based on these kind of "second act" allegations, the possibility of these kinds of claims does pose a new challenge for D & O underwriters. The underwriters must now consider whether claims might yet arise based on allegations about post-2002 late Form 4 filings and stock price increases between the grant date and the filing date. Well-advised companies will take steps now to able during their D & O insurance renewal to substantiate the timeliness of their Form 4 filings, or in general to be able to respond to questions about their regulatory filing practices. Update: A November 9, 2006 article in the Minneapolis Tribune ( here) describes a lawsuit that has been filed against Digital River, raising options backdating allegations. The allegations are based in part on Digital River's habit of being late with its Form 4 filings relating to options grants. Digital River is one of the nine companies named in the Glass Lewis study. Options Backdating Litigation Update: The D & O Diary's running tally of litigation arising from options timing allegations ( here) was updated today. According to the current tally, 95 companies have been sued as nominal defendants in shareholders derivative lawsuits based on options timing allegations. The number of options timing securities fraud lawsuits stands at 20.  Inside the Milberg Weiss Indictment: Inside the Milberg Weiss Indictment: Readers who can’t get enough of the details surrounding the indictment of the Milberg Weiss firm and two of its partners will definitely want to read the October 31, 2006 Fortune article entitled "The Law Firm of Hubris, Hypocrisy & Greed"( here). The article is written by Peter Elkind, co-author of The Smartest Guys in the Room, the standard volume on Enron's demise. The article contains detailed descriptions of the firm's interaction with the "paid plaintiffs" identified in the indictment. The article also has a fascinating account of the reaction of the key players to the criminal investigation, including in particular Mel Weiss. According to the account, as the possibility of indictment moved closer and as the firm’s negotiations with prosecutors to avoid indictment fell apart, Weiss "repeatedly assured the partnership that it faced no danger." He refused to bring in an outside firm to investigate. He also refused to turn over decisions about the investigation to nontargeted partners. And in the final stages before the indictment, the firm remained controlled by "people in the crosshairs" (including Weiss) and so refused to meet prosecutors’ demands that might have averted the firm's indictment. In other words, he was conducting himself as he has so often alleged that entrenched public company management behaves when management’s interests conflict with those of shareholders. Pretty ironic. The Fortune article makes for some pretty interesting reading, and includes a more detailed account of the facts and circumstances surrounding the Cooperman painting insurance fraud scam and its connection to the Milberg indictment, about which I previously wrote here (my prior post includes pictures of the now infamous Cooperman paintings). And Under No Circumstances Should You Read This Story: Read the story, here.

The Paulson Committee and Securities Regulation Reform

In an earlier post ( here), I commented on the initative of the so-called Committee on Capital Markets Regulation to take a look at the impact of regulation on the competitiveness of the U.S. securities markets in the global marketplace. (The Committee has become known as the Paulson Committee because of the public support that Treasury Secretary Henry M. Paulson, Jr. has shown the Committee.) An October 29, 2006 New York Times article entitled "Businesses Seek Protection on the Legal Front," ( here, registration required) takes a comprehensive look at the Committee’s efforts, and also reports some criticism that has already formed in anticipation of the Committee’s recommendations. Although the Times article is a bit vague on the details, the article reports that the Committee is looking at a number of possible reforms, including proposals to limit the liability of accounting firms; to reduce the burdens of Sarbanes-Oxley; to limit "overzealous state prosecutions"; to curtail the ability of the Justice Department to force companies under investigation to withhold paying executives’ legal fees; and to limits abusive lawsuits by investors. The article reports that "to alleviate concerns that the new Congress may not adopt the proposals... many are tailored so that they could be adopted through rulemaking." The article quotes one Committee member as saying that "the legal liability issues are the most serious…Companies don’t want to use our markets because of what they see as substantial and in their view excessive liability." The article reports that among the issues under discussion is the possible revision or elimination of Rule 10b-5. The article says that Columbia Law Professor John Coffee (a member of the Committee) has recommended "that the SEC adopt an exception to Rule 10b-5 so that only the commission could bring such lawsuits against corporations." In an October 30, 2006 Wall Street Journal op-ed piece entitled "Is the U.S. Losing Ground?" ( here, registration required), two Committee members, R. Glenn Hubbard and John L. Thornton lay out their views of the Committee’s work. (Hubbard, who was Chairman of the Council on Economic Advisors under the current President Bush, is now dean of the Columbia Business School; Thornton, now chairman of the Brookings Institution, was President of Goldman Sachs). Among other things, the authors state: The liability system can also affect the competitiveness of U.S. Markets. Firms are sometimes confronted with circumstances in litigation, including securities class action suits, where even a small probabability of loss, given the size of the claims, could result in bankruptcy. Consequently, companies often must agree to large settlements that result in reduced value for shareholders rather than pursuing a successful outcome on the merits of the case.

Clearly Hubbard and Thornton perceive securities litigation reform as a critical part of the Committee’s mission. The Committee’s report has not yet been released (according to Hubbard and Thornton, it will be released on November 30), but the Committee’s work is already the target of criticism. The Times article quotes former SEC Commissioner and Columbia Law Professor Harvey J. Goldschmid as saying "It would be a shocking turning back to say that only the commission can bring fraud cases. Private enforcement is a necessary supplement to the work that the S.E.C does. It is also a safety valve against the potential capture of the agency by industry." Professor Peter Henning of the White Collar Crime Prof blog ( here) notes that the proposal to have the SEC as the sole agent to enforce against securities fraud "would be truly radical because private actions far outnumber the enforcement cases filed by the SEC and some signicifant recoveries in private securities cases have provided relief to investors." Both Henning and Professor Larry Ribstein on his Ideoblog ( here) note that the inherent limitations on the SEC’s resources suggests that the agency alone could not be expected to enforce the securities laws. Economist and pundit Ben Stein has a much less reserved attack on the Paulson Committee’s anticipated work in his October 29, 2006 New York Times column entitled "Has Corporate America No Shame? Or No Memory?" ( here, registration required). Among other things, Stein asks "Is it really right for prominent American executives, amid a host of scandals involving other executives looting their shareholders blind, to have the best and brightest of academe and the Street lobbying for less accountability to shareholders?" (More about Stein below.) The Paulson Committee has clearly succeeded in attracting attention to its work. As a result, it is fair to describe its planned November 30, 2006 report as "much anticipated." At one level, it is perfectly understandable that leading academics and business people are focused on the competitiveness of the U.S. securities markets. But there is something more than a little bit "off" with the timing. The unfolding options backdating scandal does not exactly provide the best backdrop against which to contend that what corporate American really needs right now is less regulation. Moreover, the SEC’s hands are already pretty full. I would be surprised if anyone there were really excited about taking over the work of the entire plaintiffs’ securities bar. (I also wonder when we will start to hear from the plaintiffs' bar on these issues; I can't imagine they are too thrilled to see the possibility that their livelihood would be entirely eliminated.) The timing may be "off" in another significant respect. While the Committee plans to propose reform through regulation rather than legislation, the Nov. 7 elections could put a very interesting context around all of these efforts. If one or both houses emerge from the election with a Democrat majority, one or both houses of Congress could well perceive the Committee’s proposals for regulatory rather than legislative change as an effort by a lame duck administration to end run Congress and the democratic process. The Paulson Committee cannot pass itself off as bipartisan, and it would face all the challenges in Congress of identification with the current administration. Perhaps the Committee will anticipate these concerns when it puts its recommendations forward (it will have the advantage of knowing the election's outcome before it releases its report). But in any event, the Committee’s report will make interesting reading and could lead to some interesting developments. Stay tuned... Update: An October 30, 2006 article on Reuters ( here) contains the reactions of several promienent plaintiffs' attorneys to the proposals to reform the securities laws. Bill Lerach is quoted as saying, "Securities lawsuits have fallen off sharply in the last few years and yet they want to further cripple them. Why? Because its the one effective weapon that shareholders have." Sean Coffey of the Bernstein Litowitz firm is quoted as saying, "The body isn't even cold yet and they are already acting like there were no corporate scandals. It's mind boggling."  "The Curmudgeon's Guide to Practicing Law": "The Curmudgeon's Guide to Practicing Law": We here at The D & O Diary were delighted to see the WSJ.com Law Blog post of a very favorable review ( here) of The Curmedgeon's Guide to Practicing Law. The Guide was written by Jones Day partner Mark Herrmann, with whom I attended law school. (Not only that, his wife is my dentist.) The WSJ.com Law Blog describes the book as a well-written and clear guide on how to be an effective law-firm associate. It’s also funny: Hermann writes as The Curmudgeon, a grizzled law-firm partner who has zero tolerance for such horrors as the passive voice, long string cites and sloppy billing records. Were this material covered in some big-firm internal handbook, it would surely bore us to tears. But Hermann’s cutting wit and lively writing bring to life such painful topics as how to write a brief, how to treat your assistant and how to take a deposition.

The WSJ.com Law Blog has posted a book excerpt here, reviewing the book' s chapter on how to prepare a witness for a deposition.  Bueller? Bueller? Ben Stein actually launched his acting career ad-libbing as a high school economics teacher in the movie Ferris Bueller's Day Off. A wave file of Stein's now famous line ("Beuller? Beuller?") can be found here. Stein's own parody of the Bueller scene can be found here.

The Pre-IPO Company and D & O Risk

An October 25, 2006 article in the Raleigh, N.C. News and Observer entitled “Voyager Hit by New Lawsuit” ( here) provides an interesting example of the kinds of claims and liability exposures that officials at pre-IPO companies can face, particularly where the anticipated IPO fails to launch. Voyager Pharmaceuticals is a Raleigh, N.C.-based pharmaceutical company focused on trying to develop an experimental Alzheimer’s treatment called Memryte. Voyager had plans to raise $100 million through an initial public offering. A copy of Voyager’s S-1 can be found here. According to the news article, investors had committed $65 milion when the IPO was cancelled on December 13, 2005. A copy of the withdrawl request can be found here. Voyager recently advised shareholders that because it was unable to raise needed additional cash, it was halting the late Phase II studies of Memryte. According to the news article, Voyager filed a first lawsuit in March 2006 against Dr. Richard Bowen, Voyager’s co-founder and former Chief Science Officer. Voyager alleged that Bowen had “derailed the IPO by acting erratically and spreading false information.” On October 11, 2006, John Stone, a Voyager shareholder, filed a separate shareholders derivative lawsuit against Voyager’s CEO and CFO. This second lawsuit alleges that the defendants misled investors by inflating the company’s value. Specifically, Stone alleges that in January 2004, Bowen transferred over 1 million Voyager shares to the CEO and the CFO. Stone further alleges that even though the transfer took place in 2004, it was backdated to November 2001. Stone alleges that by backdating the transfer to a time when the shares had lower values, the beneficiaries avoided income taxes and Voyager’s net worth was overstated. In response to Stone’s allegations, the Board has formed a special committee to investigate. The Board has not yet responded. Voyager appears to have its own special set of issues and to that extent its officials' current legal woes have little to suggest for other companies. But the Voyager lawsuits do represent the kinds of unfortunate disputes that can arise when deals go bad. And at another level, the sequence of event at Voyager and the lawsuits themselves provide examples of the kinds of risk exposures that officials at pre-IPO companies face. Obviously, one risk for a pre-IPO company is that the planned IPO will not go forward, which, as the Voyager example shows, could lead to claims against senior management of the company. When a company is on a trajectory toward an IPO, there is a natural tendency to focus on the liability exposures the company will face after it goes public. But the process leading up to the IPO involves changes and circumstance that can create its own set of risks and exposures. As a company readies itself to go public, it often restructures its operations, its accounting, its debt, or other corporate features. The company also makes pre-offering disclosures, for example, in road show statements. The process also creates expectations that can create their own set of problems. All of these changes, disclosures and circumstances potentially can lead to claims, even if the offering does goes forward. Often pre-IPO company management is reluctant to take the time to address D & O insurance issues at the appropriate time before the company is deep into the IPO process. But claims can and do arise involving companies' pre-IPO activities. The significance of the pre-IPO period in a company's life cycle underscores the importance of having a skilled and experienced insurance professional involved well before the time of the IPO.  What a "Foreign Corrupt Practice" Looks Like: What a "Foreign Corrupt Practice" Looks Like: Regular D & O Diary readers will recall that I view the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act as a growing source of potential liability to companies and their senior management (most recent post on the topic here). This liability exposure is escalating as U.S. businesses are increasingly drawn into the global economy and confronting the different business standards and cultural norms in other countries. An October 26, 2006 article in the Financial Times entitled “Taking a Cut Acceptable, Says African Minister” ( here, subscription required) provides a vivid picture of how these kinds of problems can arise. The article describes efforts by a South African company to enforce a judgment the company obtained against the government of Equatorial Guinea. (Equatorial Guinea, located in West Africa and about the size of Maryland, is sub-Saharan Africa's third largest oil producing country.) The company had attempted to seize two luxury homes located in Cape Town that are owned by Teodorin Ngeuma Obiang, the son and heir-apparent of Equatorial Guinea’s President, who is also Equatorial Guinea’s forest minister. In justifying the seizure of Obiang’s Cape Town homes, the company alleged that Obiang had bought the houses with Equatorial Guinea’s government’s money, because Obiang’s $4,000/month salary as forestry minister is insufficient to permit Obiang to afford the $7 million homes. Obiang’s surprisingly candid response to the question of where he got the money to buy the luxury homes gives a stark picture of the culture of corruption that afflicts his country. Obiang declared in an affidavit that ministers and public servants in Equatorial Guinea were allowed to own companies bidding for government contracts with foreign groups, which , if successful, would permit the ministers and officials to “receive a percentage of the total contract the company gets.” This, Obiang stated in his affidavit, “means that a cabinet minister ends up with a sizeable part of the contract price in his bank account.” So here's how it works in Equatorial Guinea; you want to do business, you set up a local company -- probably not a bad idea to set up the company with the President's son. Your local company gets the contract and of course a "sizeable part" of the deal winds up in the President's son's bank account. It may not be surprising that this goes on; what is surprising is how straightforward Obiang was in describing the corrupt practices, and that he was willing to do so in a sworn document filed with a South African court. His affidavit certainly confirms the existence of rampant corruption in Equatorial Guinea. The matter-of-fact way Obiang conveyed the information suggests the challenge any company would face in trying to do business there. Corruption is simply expected. Equatorial Guinea is an oil-rich couintry. Foreign companies will be drawn there because of the country's natural resources and depleting oil reserves elsewhere. The expectation to do business Obiang’s way not only complicates the business transaction, but created liability exposures under the FCPA and under anti-bribery laws in OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries. As I have frequently noted on this blog, these exposures can also lead D & O liabilty exposures.  Among the debts underlying the South African company’s judgment is a $700,000 obligation allegedly incurred for chartering the yacht Tatoosh, owned by Paul Allen, a Microsoft founder. Tatoosh is 300 feet long, has a crew of 30 and has auxiliary vehicles that include two helicopters, a submarine, and a separate 54-foot racing yacht. It also has its own swimming pool. A September 6, 2006 Times of London article about Obiang that describes the Christmas party for which Obiang hired the use of Tatoosh, entitled "Playboy Waits for His African Throne," may be found here. Special thanks to a loyal reader for the link to the Financial Times article. What a Coincidence, Terrorists Have Been Stealing the Beer from My Refrigerator: A New Jersey real estate attorney has sued his malpractice carrier for refusing to reimburse him for amounts he had to pay to make up for lost funds in his client trust account. The attorney claims that because he was “extremely busy” from 2000 through 2002, he “failed to reconcile his trust account on a regular and timely basis.” He alleges that he learned in July 2002 “that a terrorist group had over a period of time duplicated checks and forged Plaintiff’s signature to obtain the funds in question.” When he discovered the missing funds, the attorney used his own and borrowed funds to protect his clients from losses. He settled with his bank for $95,000. His suit seeks to force his insurer to pay the remaining amount. The attorney’s complaint, which may be found here, does not name the terrorist group.

Institutional Plaintiffs’ Impact on Securities Litigation

For those of us who must try to understand securities litigation trends, one of the developments worth watching closely has been the impact of institutional plaintiffs (mostly public pension funds) on securities litigation. It has been apparent for some time that cases with institutional lead plaintiffs usually resulted in larger settlements, but the question remained whether this was really the result of institutional plaintiff involvement or just a by-product of institutions choosing to become involved in the largest and most meritorious cases. An October 2006 paper by St. John’s University Law School professor Michael A. Perino entitled "Institutional Activism Through Litigation: An Empirical Analysis of Public Pension Fund Participation in Securities Class Actions" ( here) examines "whether public pension fund monitoring is effective"; specifically, Perino examined "whether there is any correlation between cases with public pension fund lead plaintiffs and settlement outcomes, attorney effort, or fee requests or awards." Perino used statistical techniques in reviewing class action data to control for potential institutional self-selection of larger, more meritorious cases and other factors that might affect settlement outcomes and fee awards. Perino’s paper has three findings: First, cases with public pension participation are positively correlated with settlement amounts (measured both in absolute terms and as a proportion of investors’ overall market losses), even when controlling for institutional self-selection of larger, more high profile cases.

Second, cases with public pension lead plaintiffs are positively correlated with two proxies for attorney effort, the number of docket entries in the case and the ratio of settlement to docket entries, suggesting that institutional monitoring may reduce attorney shirking.

Third, attorneys’ fee requests and fee awards are lower in cases with public pension lead plaintiffs, either because public pensions are sophisticated repeat players or as a result of attorney competition to represent these institutions.

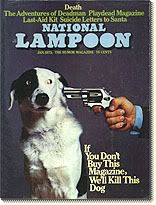

Perino concludes that "[t]he findings suggest that public pension funds do act as effective monitors of class counsel" and that "public pension fund participation as lead plaintiffs in securities class actions appears to have many benefits Congress anticipated" in enacting the PSLRA. These findings are important because public pensions are playing an increasingly larger role in securities class action lawsuits. According to the 2005 PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Securities Litigation Study ( here), public pension funds served as lead plaintiffs in over 40% of the securities class action lawsuits filed in 2005, which is up significantly from the percentage in the early years immediately after PLSRA’s enactment. (For example, public pensions served as lead plaintiffs in only 10.3% of the cases filed in 2000.) Many studies, including the PricewaterhouseCoopers study, have observed that average securities class action settlements have increased in recent years. If an important factor in this increasing average severity is the involvement of pension fund plaintiffs, and if pension fund increasingly are serving as lead plaintiffs, then Perino’s findings have important implications for D & O carriers’ expected severity (particularly excess carriers’ expected severity). However, as Perino’s study notes, pension funds "will continue to appear predominately in the largest cases where the benefits of monitoring are most likely to outweigh the costs." In other words, pension funds are unlikely to become involved in smaller cases; it may be that these cases will simply not be filed, which may in part account for the observed decline in class action frequency in 2006. Hat tip to Adam Savett at the Lies, Damn Lies blog for the link to the Perino paper. Savett's interesting commentary on Perino's paper may be found here. The Best Coverage: According to an October 24, 2006 New York Times article ( here, registration required), a panel of the nations’ magazine editors and designers has chosen a New Yorker cover depicting President Bush being flooded in the Oval Office after Hurricane Katrina as the best magazine cover of the year. While we like that cover, we don’t think it will crack into the list of the American Magazine Conference’s Top 40 Magazine Covers in the Last 40 Years, which may be found here. This list includes some covers that you will smile to see again. You may disagree with the order in which the covers are listed, but you won’t disagree with the selection overall.  The D & O Diary The D & O Diary is partial to the National Lampoon’s January 1973 cover (No. 7 on the list), "If you don’t buy this magazine, we’ll kill this dog." Special thanks to a loyal reader for the link to the Top 40 site.

Tracking Options Backdating

According to news reports ( here), Glass Lewis has released an analysis estimating that the options backdating scandal now involves 152 companies and has cost those companies collectively about $10.3 billion. A breakdown of the 152 companies can be found here. CFO.com reports here that so far over 60 companies have announced accounting restatements in connection with options timing issues, totaling $5.2 billion in accounting charges. Another 24 companies have announced they will have to restate earnings, but have not yet announced the amount of any charges. The scandal has also cost over 40 executives their jobs. The WSJ.com has a separate page ( here) where they are keeping an updated list of the executives' ousters resulting from the backdating scandal. The D & O Diary's list of options backdating lawsuits ( here) has been updated today. The number of options timing related shareholders' derivative suits now stands at 92. The number of options timing related securities fraud lawsuits remains at 20. The Stanford Securities Class Action Clearinghouse has added a box to its home page ( here) in which it is also tracking the number of options timing related securities class action lawsuits; its tally also stands at 20.

The End of an Era?

According to an October 25, 2006 Washington Post article entitled "End of Enron’s Saga Brings Era to a Close" ( here, registration required), the sentencing of former Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling "closed the book on an era of high profile corporate malfeasance." Among other things, the Post article reports that "[h]ours after a judge sentenced Skilling…the leaders of the Enron task force announced they would close up shop, saying their mission was mostly complete." But does the Skilling sentencing and the winding up of the Enron task force really mean the end of an era of high profile criminal prosecutions? Even the Post article itself is quick to point out that a fresh wave of scandals already under way suggests that white collar fraud prosecutions will remain an important part of the judicial landscape for the foreseeable future. This week’s guilty plea of Comverse Technology’s former CFO in connection with the company’s options backdating investigation ( here), and the indictment of REFCO’s former CFO ( here), are but the latest signs that white collar crime will remain a high prosecutorial priority. For that matter, even though Skilling’s sentencing might represent a high water mark, it is far from the end of the Enron saga. As detailed in an October 24, 2006 Houston Chronicle article entitled "Other Trials Likely; Shareholder Suit on Tap" ( here), there are still quite a number of Enron-related criminal prosecutions remaining in the pipeline. For example, three British bankers, extradited to the U.S. earlier this year, will stand trial early next year on allegations that they stole from a former employer in connection with an Enron-related transaction. There may be new trials for several former Enron executives whose trials ended in mistrials. Several key Enron defendants, including former Enron Chief Accounting Officer Richard Causey, are yet to be sentenced. The civil lawsuit against former Enron investment banks (at least the ones that have not already settled) and the Houston law firm of Vinson and Elkins remains pending. And even when the book is finally closed on Enron, whenever that may be, the assault on white collar fraud is likely to continue. In one of the more interesting quotations in the Post article cited above, Timothy J. Coleman, a former prosecutor and Justice Department official who, while at DOJ, was responsible for the President’s Corporate Fraud Task Force and supervised the work of the Justice Department’s Enron Task Force and Criminal Fraud Section, predicted that: The legions of investigators hired by securities regulators, federal prosecutors and the FBI will pay lasting dividends because they will become a "standing army" ready to target business wrongdoing. "Whether it’s stock options, mutual funds or something else, corporate America should expect a continuing series of major, nationwide investigations for the foreseeable future," said Coleman. A "standing army" is expensive to maintain. It also has to justify its existence. Reasonable minds may question whether a permanent corporate crime military force is really in the best interests of investors, and what effect it will have on America's competitiveness in the global economy. The standing army may be one of the least attractive legacies of Enron. (Consider what the Enron Task Force did to Arthur Anderson. ) More comments on the "standing army" follow below. The D & O Diary’s prior comments on Enron’s Legacy can be found here.  Skilling’s Sentencing: Comment from the Blogosphere: Skilling’s Sentencing: Comment from the Blogosphere: Skilling’s sentence provoked a wide variety of comments in the blogosphere (links to blog posts here; The D & O Diary’s post on the topic can be found here.) But the most interesting comments appear on the White Collar Fraud blog ( here). Regular D & O Diary readers will recall that the White Collar Fraud blog is maintained by none other than Sam E. "Sammy" Antar, the former CFO of Crazy Eddie’s. (See my prior post about Antar here). Antar states: The sentencing of Mr. Skilling will not stop any crimes in progress or cause any criminal to wake up the next day with any new found morality. Criminal can only be prevented through effective deterrents through barriers such as strong internal controls, effective oversight, and "checks and balances." In an earlier post ( here), Antar wrote: No criminal changes their moral compass and no crimes in progress are stopped as they read about long prison terms imposed on felons like Bernie Ebbers…However, as an ex-felon I can say that criminals fear barriers such as a strong internal control structure, well educated, skilled, and trained external public accountants who are truly independent. Criminals fear oversight. White collar criminals think in terms of the successful execution of their crimes (like a project) and are undeterred by strong prison sentences (which we require to exact responsibility and accountability on criminals, but are not a significant preventive measure).

Antar’s concluding remarks in his post about Skilling’s sentence: Punishment and prison are important. However, unless integrated with prevention, professionalism (competence), and power (legislation), there will be many more Enrons to come.

Antar’s comments ring true to me. They also raise questions about the wisdom of maintaining a "standing army" to prosecute the perpetrators of the future Enrons, as opposed to concentrating on trying to prevent future Enrons from occurring in the first place. Resources and efforts would be better invested in trying to deter and prevent wrongdoing rather than punishing it once it has occurred. Vast resources tied in up in a "standing army" devoted to finding people to punish and then punishing them is a misallocation of social assets.

Enron in Cyberspace: As noted in the Daily Caveat (here), there is a "ridiculously cool" Enron Explorer website (here), that contains a searchable, graphically relatable database of over 200,000 emails that traversed through Enron as it careened toward oblivion. I recommend this site; it is unspeakably weird to be able to get lost inside an unfolding American corporate catastrophe. The WSJ.com Law Blog has isolated a few of the "highlights" (here), such as this sarcastic excerpt: "Certainly all of you can stop shredding documents for 5 minutes to respond." It is Always About Harvard (Just Ask a Harvard Grad): Enron is no exception. Details on the Harvard connection to Enron, here.

Developments in Outside Director Liability

As the various corporate scandals have unfolded, one of the concerns has been whether changing laws and attitudes may mean that outside directors face increased exposure to shareholder claims and enforcement actions. (See my prior article on the topic here.) One of the elements of this concern has been the statements of various regulatory officials that they intend to pursue outside directors for their failure to prevent corporate officials’ misdeeds. Among the oft-cited recent examples of regulatory intent to pursue outside directors is the December 2005 service of a " Wells Notice" on three outside directors of the Hollinger. But whatever regulators overall intent may be regarding outside directors generally, the SEC has recently advised the three Hollinger directors that it will not pursue enforcement action against them. The SEC has been pursuing an enforcement action ( here) against Hollinger’s former chairman and CEO Conrad Black and its former COO F. David Radler. In addition the Department of Justice has filed criminal charges against Black, Radler and other individuals. ( Here) Radler has pled guilty to the criminal charges, but the civil and criminal charges against Black remain pending. Essentially, it is alleged that Black and Radler defrauded Hollinger’s shareholders by diverting the company’s assets and opportunities (in simple terms, they are alleged to have looted the company). Hollinger’s Board ousted Black in November 2003. According to news reports ( here), in December 2005, the SEC served Wells Notices on three members of Hollinger’s board. The three individuals included Jim Thompson, the former Governor of Illinois; Richard Burt, who served as U.S. Ambassador to Germany under Ronald Reagan; and Marie-Josee Kravis, an economist and wife of financier Henry Kravis. The three made up the board’s audit committee at a time when Black allegedly was fleecing the company. But while the service of the Wells Notice on the Hollinger directors seemed to suggest a regulatory intent to pursue outside directors, it now appears that the SEC does not intend to go after the Hollinger directors after all. In an October 20, 2006 Chicago Tribune article entitled "SEC Drops Probe of Thompson" ( here), the individuals stated that the SEC had recently advised them that it would not pursue legal action against them. In a separate development, Richard Perle, another former Hollinger director who had also received a Wells Notice, also announced that he had been advised by the SEC that it would not pursue an action against him ( here). The SEC's decision not to pursue Perle may be even more significant, because Perle had served on Hollinger's board's Executive Committee with Black and Radler. According to news reports, Hollinger's own internal investigation had concluded that Perle had "repeatedly breached his fiduciary duties" by failihg to evaluate consent forms that authorized transactions. The SEC’s decision not to pursue further enforcement actions against the Hollinger outside directors is consistent with expectations based on historical practices. According to a 2006 legal study by University of Texas Professor Bernard Black, Cambridge University Professor Brian Cheffins, and Stanford Law School Professor Michael Klausner, entitled "Outside Director Liability" ( here), the liability risk of outside directors is "very low." The article details the infrequency with which outside directors are the target of enforcement proceedings and liability actions. The remote possibility that Outside Directors might be called upon to contribute to settlements out of their own funds, "would be avoided with appropriate [D&O] policy limits and current state of the art protections." Nevertheless, it remains to be seen whether the current options backdating scandal will result in enforcement actions or liability exposure against outside directors. For example, three directors of Mercury Interactive have themselves been served with Wells Notices in connection with the company’s options backdating investigation. ( Here). (Mercury itself has proposed the pay a $35 million civil penalty, here.) In addition, according to news reports ( here), in the recent shareholders’ derivative action filed against Novell, plaintiffs’ lawyers have indicated their particular aim to pursue board members in connection with the allegedly backdated options the board received. Options Backdating and D & O Insurance: One of the recurring questions as the options backdating scandal has unfolded has been what the scandal may mean for D & O insurers – and their policyholders. On October 20, 2006, the San Francisco Chronicle ran an article entitled "Who Pays Mounting Legal Bills? Insurers May Cover Directors, Execs – For Now" ( here). The article discusses likely D & O coverage issues and concerns from the options backdating scandal. Full disclosure: I was interviewed in connection with the article. Conrad Black on FDR: Apparently Black has had a lifelong interest in Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and among the things for which Black is alleged to have used the funds he misappropriated from Hollinger is an auction purchase of a collection of FDR's papers. With the assistance of his wife, conservative columnist, Barbara Amiel, Black wrote a bestselling 1,280-page biography of FDR entitled Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Champion of Freedom. The book received generally positive reviews ( here). On October 29, 2003, shortly before he was ousted from Hollinger, the Wall Street Journal published an op-ed column written by Black, entitled "Capitalism's Savior" ( here), in which Black extols FDR's virtues and asserts that FDR is "rightly judged the greatest American president since Lincoln." A January 12, 2004 New York Magazine article examining the curious intersection between Black's literary pretensions and his legal woes may be found here.

Skilling's Sentencing

On Monday October 23, 2006, the final chapter in the Enron criminal saga will conclude when Judge Sim Lake sentences former Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling. Pundits’ estimates of Skilling’s likely sentence range from 20 to 25 years ( here). The accumulated anger of the legions of Enron employees and investors seem to require a harsh sentence. But even given the consensus view that Skilling is the bad guy in the Enron story, circumstances have conspired to put Skilling in an even worse position for his sentencing. It is nearly impossible to want to rally to Skilling’s defense, but something – perhaps just an instinctive impulse to be contrary – compels me to wonder whether Skilling might receive a sentence based on factors other than his just deserts. Within the narrative framework of the 21st century morality play that the Enron criminal trial has become, Skilling’s role is unmistakable. His arrogance and greed border on caricature. All he needs is a cape and a curled mustache to turn him into a cartoon of a bad guy. Stories about how big a jerk have collected around him since Enron’s collapse. Legend has it that in response to a Harvard Business School entrance interview question whether Skillling was smart, he supposedly responded, "I’m fucking smart."( here) During an April 2001 recorded analyst conference call, one of the analysts questioned Enron’s accounting practices, commenting that Enron was the only company that released its earning statement without a balance sheet, to which Skilling replied, "Well, thank you very much, we appreciate that …asshole." ( here) In response to his criminal prosecution, Skilling has been unwaveringly defiant and remorseless. He disregarded his lawyer’s advice to refuse to answer questions based on his Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination, but instead answered every question posed to him by Congressional investigators. He even submitted to a lengthy SEC interview. Skilling has managed to make things even worse for himself by getting arrested twice, once before the trial ( here) and once after the trial ( here), in alcohol related incidents involving disorderly conduct and public drunkenness. Skilling’s character and conduct have virtually assured him an unfavorable sentencing profile. But as bad all of that is, circumstances that should have nothing to do with his sentencing have put him in an even worse position. First, Ken Lay’s July 2006 death has left Skilling as the last man standing. Enron employees, furious that Lay cheated the hangman, and even angrier that Lay’s conviction was abated, are demanding that Skilling be punished for Lay’s crimes as well as his own. According to former federal prosector Robert Mintz ( here), "In theory, the death of Ken Lay should have no impact on the sentence that Mr. Skilling receives. But it's hard to ignore the reality that Jeff Skilling is now standing alone as the figurehead who orchestrated Enron's demise. There will certainly be pressure to make an example of Jeff Skilling and send a message with his sentence.'' Second, Andrew Fastow’s conspicuously lenient sentence left former Enron employees enraged. ( here). The perception that Fastow pulled a fast one on the Court (which apparently has left the government considering the possibility of appealing Fastow’s conviction, here) has united public opinion in the view that Skilling at least must be made to pay, and perhaps make up for the fact that Fastow got off light. Adding to all of this is the prosecutorial feelings of vindictiveness against Skilling for his steadfast refusal to acknowledge guilt or show any remorse. Skilling seems to have done everything he can to antagonize the government, even referring to them in a post-trial interview ( here) as "the Gestapo." So if the over/under on the length of Skilling’s sentence is twenty years, the smart money is betting on the over option. There is no doubt that Skilling must receive a lengthly prison term. He was found guilty on 19 of the 28 counts against him, including one count of conspiracy, one count of insider trading (although he was acquitted on nine other insider trading counts), five counts of making false statements to auditors, and twelve counts of securities fraud. Each conviction carries a maximum sentence of 5 to 10 years in prison. His conviction of these crimes required that he serve a substantial period of incarceration. But while Skilling’s crimes demand a substantial punishment, he should not be punished for any of the swarm of other factors surrounding his sentencing. His well-deserved reputation for arrogance and greed should not affect the length of his sentence. (If arrogance or greed were punishable offenses, most of Wall Street would be behind bars.) His insistence on exercising his constitutional rights to a presumption of innocence and to a jury trial should not increase the length of his sentence. His guilt is no greater because it was determined by a jury verdict rather than by his own admission in the form of a guilty plea. Nor should his sentence be affected by what happened after the trial to Lay and Fastow. When Skilling stands in the dock to receive Judge Lake’s sentence, he will stand alone. He should be punished for his crimes, but only for those for which he himself has been found guilty. He should not bear a heavier punishment because others evaded their just penalty. Skilling will go to jail for a very long time no matter what happens. But the time he serves should reflect only the crimes for which he was convicted -- and nothing more. Update: On October 23, 2006, Judge Lake sentenced Skilling to 24 years and four months in prison. Judge Lake estimated the shareholder loss that Skilling had caused at $80 million, which under the applicable federal sentencing guideline indicated a sentence in the range of 24.3 years to 30.4 years, so Skilling's sentence was at the low end of the indicated range. An October 23, 2006 New York Times article describing the sentencing can be found here. Interesting commentary in the White Collar Crime Prof blog about the Skilling sentence can be found here.

Latest Options Backdating Dispatches

The options backdating story has unfolded in successive stages. First, there was the March 18, 2006 Wall Street Journal article ( here, registration required) that drew attention to the issue and set off the media frenzy. Then there were the waves of announcements from companies stating that they or regulators were investigating their options practices. (According to the WSJ.com "Options Scorecard," here, there are 115 companies under investigation one way or the other.) The current stage seems to involve the slow but steady defenestration of numerous senior company officials. An October 17, 2006 Philadephia Inquirer article entitled "Backdating –Who Has Been Ousted" ( here), attempted to list all of the executives who have lost their jobs so far. Even thought the Inquirer list is only a couple of days old, it is already out of date, because it omits the recent departures from KLA-Tencor ( here and here), Altera ( here), Sapient ( here) and SafeNet ( here). By my count, more than 40 executives have lost their jobs so far. More departures undoubtedly are on the way. These circumstances have to be uncomfortable for executives at companies undergoing options timing investigations. Both investors and the individuals themselves have to be wondering about the executives' continued tenure. For example, the San Jose Mercury News ran an October 17, 2006 article entitled "Is Steve Jobs Safe?" ( here, registration required) (short version: not enough information yet). Times have to be rough even for executives whose names are not in the papers every day. There is a certain inevitability to this ritual bloodletting. The companies are, of course, taking great pains to repair their public image and to restore investor confidence. Companies also face pressure under the Thompson Memo to show full cooperation with regulators in order to avoid corporate criminal prosecution, which adds a particularly sharp edge of necessity for companies to cut individuals loose. Given the number of companies that have not yet completed their investigations, the steady drumbeat of executive departures is likely to continue for some time. There is some peculiarly American necessity to scapegoat and assign blame when dramatic, unexpected events occur, and consistent with that tradition it is to be expected that these company officials are being made to walk the plank. Perhaps few will shed tears for William McGuire, United Health Group's recently departed CEO, who ended last year with $1.78 billion in unexercised stock options. But SafeNet’s October 18 announcement ( here) of the resignation of two of its officials (including one of its founders) has a downright elegiac tone. The D & O Diary questions whether this forced exodus of the senior officials at so many companies is really in investors’ best interests --or in anyone's best interest. This concern will only grow as the list of ousted officials lengthens in the weeks and months ahead. Finally, if the current stage in the unfolding backdating story is the outster of senior officials, what is the next stage? Possibilties include additional criminal and regulatory enforecement actions and resolution of the pending civil litigation, undoubtedly followed by coverage disputes. Regardless of what lies ahead, this story has a very long way to go yet. We are still only in the opening chapters. Options Backdating Litigation Update: Along with the steady stream of executive departures has been the continuing influx of new options backdating lawsuits. According to The D & O Diary’s latest tally ( here), there have 20 securities fraud lawsuits and 89 shareholders’ derivative lawsuits based on allegations of options timing misconduct. Harvey Pitt Interview: In an interview published in the San Jose Mercury News on October 17, 2006 ( here, registration required), former SEC Chairman Harvey Pitt had a number of interesting observations about the unfolding options backdating story: This may be just my own inherent bias, but I have very little sympathy for the companies that were engaged in real backdating. If you look at the Brocade and Comverse indictments, that conduct was raw. I grew up in Brooklyn, and we had a word for that. We called it fraud….

On the other hand, there are cases where people made mistakes, maybe cases where people did things inadvertently, maybe cases where companies backdated option grants but had poor procedures. That's where the tension comes into play. It places a heavy premium on regulators and prosecutors to be balanced in their judgments. Just because there was backdating doesn't mean it was a hanging offense. But if it was backdating with false documents and that sort of thing, I do think it's a hanging offense….

Then you also need to look at what the company is doing -- how does the company rectify the situation? If what you want is for companies to be law-abiding, then you have to give them credit when they take steps to bring themselves into compliance.

The SEC is showing a great amount of balance in how it approaches these issues. It's not rushing to make headlines. It's proceeding in a way that is thoughtful and appropriate. That is the hallmark of good regulation and good enforcement. Pitt is right that a distinction needs to be drawn between companies that falsified documents and companies that made inadvertent mistakes due to poor procedures. All too frequently the media tar both kinds of companies with the same brush. I also hope he is right that the reason the SEC has been moving deliberately in its investigations of options backdating is that it is attempting to draw these kinds of distinctions. Word Czech: While the word " defenestration" is generally meant to refer to the act of throwing someone out of the window, historically the word was meant to suggest politicial dissent.  The historical reference derives from the "defenestrations of Prague," particularly the Second Defenestration of Prague, which took place in 1618, during the Thirty Years War. Protestant aristocrats, angered by Catholic Church attempts to claim certain contested land rights, convicted several officials for violating the rights of religious expression and threw the officials from the windows of the Bohemian Chancellery. According to tradition, the officials landed in a pile of manure-- and survived. With that historical background, readers may judge for themselves whether it is accurate to refer to the backdating-related ouster of corporate executives as defenestration. According to Merriam-Webster ( here), "defenestration" was one of their dictionary's users’ favorite words of the year in 2004. By the way, the 2004 Word of the Year was "blog." Now you know.

More About Board Turmoil and D & O Risk

In recent weeks, the Hewlett-Packard (H-P) board has struggled to manage the turmoil and adverse publicity from its flawed investigation of media leaks. While the H-P debacle may be the most notorious recent example of board tumult, it is merely one of many instances of problems arising from increased tension inside numerous corporate boardrooms. By way of illustration, since early 2005, the boards of some of the country’s largest companies have ousted their CEOs – including Bristol-Myers Squibb, Fannie Mae, Pfizer, Merck and American International Group (AIG). In the October 2006 issue of InSights ( here), I discuss how board turmoil not only generates distraction and adverse publicity, but also increases the possibility of D & O claims activity. A prior D & O Diary post on board turmoil and D & O risk can be found here. Significant FCPA Enforcement Developments: In the past few days, there have been two significant Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) enforcement developments. First, on October 13, 2006, the SEC announced ( here) the institution of a settled enforcement action against Statoil ASA, a Norway-based company whose shares are traded on the NYSE. The SEC found that Statoil had paid bribes to an Iranian official in return for his influence to help Statoil obtain contractual development rights to Iranian oil and gas fields. Without admitting or denying the allegations, Statoil agreed to pay disgorgement of $10.5 million In a related criminal proceeding, Statoil agreed to pay an additional $10.5 million penalty as part of a deferred prosecution agreement. ($3 million of the $10.5 million penalty was deemed satisfied by Statoil’s prior penalty payment to Norwegian officials). On October 16, 2006, Schnitzer Steel Industries agreed to pay $15.2 million resolving an investigation that commenced with the company’s self-reporting of improper payments made between 1999 and 2004 in connection with the company’s operations in China and South Korea. The company’s press release is here. The company’s deferred prosecution agreement requires the company to hire an independent compliance consultant to audit and monitor the company’s operations. I have frequently posted about the growing risk of FCPA enforcement actions (most recently here). The dollar size of these two recent settlements show the seriousness and magnitude of these actions. The Statoil case shows that both foreign and domestic public companies are subject to the FCAP if their stock trades on American exchanges. And the Schnitzer Steel case shows the growing role of self-reporting as a growing source of increased enforcement activity. "The Funniest Joke in The World": Watch the Monty Python video here. Read the Wikipedia article here.

Securities Litigation Reform Redux?

When the soi-disant "Committee on Capital Markets" announced ( here) on September 12, 2006 that it was forming an independent group of business and academic leaders to study how to improve the competitiveness of U.S. capital markets, the press coverage ( here) generally presumed that the group would be focused on reforming the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. But in the Committee’s press release describing the study group’s mission, Sarbanes-Oxley was the second item on the list; the first item listed was "[l]iability issues affecting public companies and gatekeepers (such as auditors and directors) with a focus on securities class action litigation, criminal enforcement and federal versus state authority." (The Committee's press release included a statement of support from Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, and so the Committee has come to be known as the "Paulson Committee.") An October 16, 2006 post on the Securities Litigation Watch entitled "'Paulson Committee' May Soon Recommend Dramatic Limits on Securities Class Actions"( here) attributes a number of statements from Columbia Law School professor and Committee member John Coffee about the Committee's prospective suggestions to mitigate the threat of securities litigation. Coffee reportedly expects the group to make recommendations to "impose limits on securities class actions" and that the "SEC could take action to change the role of the securities class action" within 6 months. According to the Securities Litigation Watch, Coffee has said that the possible alternative changes that could be proposed include the following: 1. The SEC could "dis-imply" a private cause of action under Rule 10b-5 against corporations, leaving enforcement of that rule to the government, not private plaintiffs. The SEC might also "dis-imply" such a private cause of action with respect to the corporation only when the SEC has sued the corporation. Coffee states… that "That idea does have some support."

2. "Stock drop" cases could be moved out of the courts and into the arbitration arena.

According to the Committee’s September 12 press release, the group plans to release recommendations to key policy makers for specific changes in regulation and legislation by the end of November. The intervening Congressional election could have some impact on the Committee’s recommendations’ prospects for success. There is every possibility that after the election the Democrats could control one and possibly both houses of Congress. While the Committee’s membership of academics and corporate leaders gives it the air of independence and disinterest, the group is associated with the current Treasury Secretary and does include some Republican affiliation (e.g., former Secretary of Commerce Donald Evans), but lacks any obvious Democratic affiliation, so the Committee seems unlikely to be able to call itself bipartisan. Moreover, while the Committee’s membership is prestigious, it omits any representation of shareholder groups, labor unions or others who might oppose easing legislative or regulatory constraints. Any recommendations for radical change that could emerge from the group would likely face the prospect both a sharp reaction from other constituencies and could also face a hostile Congress. In any event, the prospects for securities reform while the options backdating scandal continues to play out on the front pages of the newspapers seems questionable. Nevertheless, it will definitely be interesting to see what the Committee comes up with. Add this one to the list of "Things to Watch." Adding Inquiry to Insult: A resource for just the right slight, here.

More About the FCPA and D & O Risk

In prior posts ( here and here), The D & O Diary has written about the increasing level of Foreign Corrupt Practices Act enforcement activity and the growing D & O risk that it represents. An October 4, 2006 opinion in the United States District Court in Atlanta by Judge William Duffey Jr. in the consolidated Immucor securities litigation (view complaints here) illustrates how the increased level of FCPA enforcement activity can lead to heightened D & O risk. Plaintiffs sued Immucor and two of its officers (a third individual defendant died after the Complaint was filed and was dismissed from the action). The Complaint alleges that between August 16, 2004 and August 29, 2005, the defendants made numerous statements about corruption problems at Immucor’s Italian subsidiary. The plaintiffs did not allege that the defendants failed to disclose the existence of problems; rather, the plaintiffs allege that in SEC filings, press releases and conference calls with stock analysis, the defendants misled potential investors into an over optimistic assessment of Immucor’s corrupt foreign business practices and the strength of Immucor’s internal control mechanisms. An unusual aspect of this case is the allegation that one of the individual defendants was head of the Italian subsidiary at the time the alleged bribes took place, prior to his becoming Immucor’s CEO, and therefore this individual (and by extension Immucor) had actual knowledge of the falsity of the misrepresentations at the time they were made. The defendants moved to dismiss the Complaint on the grounds that the plaintiffs had not alledged any false or misleading statements, and on the grounds of scienter and failure to adequately plead loss causation. Judge Duffey denied the motion to dismiss as to several of the allegedly misleading statements. Even though the company disclosed the existence of an Italian criminal investigation and an internal investigation of allegedly improper payments, the Judge found that these disclosures created the impression that the investigation was limited to a single incident of poor bookkeeping by Immucor …but Plaintiffs allege that multiple legally dubious payments made by De Chirico [the former head of the Italian subsidiary and CEO at the time the alleged misstatements were made] or under his direction were being investigated. The omission creates a distorted picture of Immucor’s alleged liabilities. That is, while parts of the disclosure may have been accurate, Defendants’ duty was to describe fully the nature and scope of the conduct under investigation – conduct of which De Chirico was fully aware because he participated in it. The omitted information would have been viewed by a reasonable investor as affecting the total mix of information available, and a reasonable investor’s investment decision would have been swayed had the alleged omitted information been included in the press release.

Judge Duffey also found that the allegations of actual knowledge represented sufficient allegations of scienter to survive a motion to dismiss, and that the plaintiffs had adequately pled loss causation. As The D & O Diary noted in its prior posts, the D & O risk arising from FCPA actions is not so much due to the enforcement proceedings themselves, since any fines or penalties likely would not be covered under the typical D & O policy; rather, the risk arises from the follow-on civil actions. The Immucor case, while it has some unusual features, illustrates how these follow on civil actions can arise. Plaintiffs’ allegations in the Immucor case that the defendants did not fully disclose the extent of the company’s FCPA exposure is not in and of itself unusual in securities litigation, as securities cases often allege that defendants soft-pedaled or minimized adverse information. However, the increasing level of FCPA enforcement activities provides increasing opportunities for these kinds of issues to arise. That is one reason why The D & O Diary has identified the increase in FCPA activity as one of four D & O trends to watch ( here). One particular feature of Immucor’s circumstances explains why FCPA activity is increasing. That is, Immucor itself identified the existence of potentially improper payments and self-reported the payments to the SEC. This type of self-reporting is one of the causes behind the increase in FCPA activity. Due to the requirements of Sarbanes Oxley, companies are undertaking a more thorough operational review, including review of their overseas operations, and are finding a greater number of concerns. As a result of guidelines requiring self-reporting in order to avoid corporate criminality, more corporations are turning themselves in. (There is more than a little irony in the fact that having self-reported to the SEC, Immucor is now accused of withholding information.) FCPA enforcement activity because more companies are turning themselves in for violations they have found themselves. An October 12, 2006 memorandum from the Wilkie, Farr & Gallagher law firm discussing the Immucor case and the ruling on the dismissal motion can be found here. Bad News Disclosure: The Immucor case is also a good illustration of the pitfalls that attend bad news disclosure. (The allegations in the Immucor complaint of course remain unproven; for purposes of the motion to dismiss, and for purposes of this discussion, the allegations are taken as true.) As I have written elsewhere about the pitfalls of bad news disclosure ( here), "partial, incomplete or overly optimistic disclosure can exacerbate the damage from bad news disclosure and risk the creation of securities litigation exposure." As bad as the consequences of bad news are, they can always be made worse by attempts to bury the news. As the Immucor case demonstrates, the risk from trying to put positive "spin" on bad news is that it may later be alleged that the "calming statement" itself is misleading – in other words, the securities litigation arises from the "damage control," not the underlying event. Today’s Stat: According to The Economist magazine ( here, subscription required), "The State of California alone has more venture capital than any country outside the United States."

Notes from Around the Web

The D & O Diary has had numerous posts commenting on the possible reasons for the YTD 2006 decline in the number of securities class action lawsuits (most recent post here). D & O maven and prominent coverage attorney Dan Bailey of the Columbus, OH law firm of Bailey Cavalieri has recently formulated his own explanation for the declining number of suits, in his article "Why Are There Fewer Securities Suits?" ( here). Dan’s article is, as usual for Dan’s work, well-written and thorough. Dan attributes the drop to a number of contributing factors, most of which he views as merely temporary. Among the factors he considers are the recent reduction in stock price volatility, enhanced corporate governance and the Dura decision. He is skeptical that the Milberg Weiss indictment has had much impact on the number of securities suits, and thinks that any diversion of plaintiffs’ lawyers’ attention based upon their filing of options backdating related derivative suits will be purely temporary. Because Dan regards many of the causes of the current lawsuit decline as temporary, he believes that it is "extremely unlikely" that this decrease in shareholder litigation will be permanent and therefore "neither D & O Insurers nor Insureds should overreact to this seemingly temporary reprieve from higher-frequency securities litigation." He also specifically notes that "an over-reactive softening of the market today in response to this development will likely cause another significant market correction in a few years." Readers should be aware that Dan’s firm’s website has an archive of Dan’s other D & O-related writings ( here, scroll down to "Director and Officer Liability") His articles are uniformly interesting and well-written, and collectively represent a useful resource on D & O liability issues. Special thanks to Dan for providing a copy of (and a link to) his article. Pay Scale: According to an October 12, 2006 article in the Rocky Mountain News ( here), the Lerach Couglin firm sought $96 million in legal fees for its role as lead plaintiffs’ counsel in connection with the $400 million settlement of the Qwest Communications securities class action lawsuit. Denver attorney Curtis Kennedy, representing the Association of U. S. West Retirees, succeeded in getting the legal fees cut to $60 million, providing $36 million more for the shareholders. Kennedy’s fee? $40,500. Seems like there might be an ironic parable about "value for value" here... FCPA Perspective: Regular readers know that the D & O Diary has frequently written about the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, and the growing importance that the FCPA has for D & O risk (most recent posts here and here). Alert reader Winnie Van called our attention to an article that appeared in the San Francisco Business Times entitled "Feds Take Aim at Bribery" ( here). The article documents the recent sharp spike in FCPA enforcement activity, which the article attributes in part to the growing importance of doing business in India and China, as well as the increased scrutiny on operations and controls under Sarbanes Oxley. The article also discusses that several major law firms and accounting firms have been gearing up to address their clients’ issues under the FCPA, because they see it as a growing threat. As The D & O Diary has noted, the FCPA is also a growing area of potential D & O risk ( here). Blog Alert: The many D & O Diary readers who are involved in insurance coverage counseling and litigation may be interested to take a look at the Insurance Coverage Law Blog ( here). While the blog does not specifically address professional liability coverage issues, it does generally have interesting posts and links related to insurance coverage issues. Hat tip to Adam Savett at the Lies, Damn Lies blog for the link. Why Google Bought YouTube: If, like The D & O Diary, you find yourself wondering what Google could possibly have been thinking when it agreed to pay $1.65 billion for YouTube, perhaps a glance at this Google-generated "trends" chart ( here) might illuminate what was on Google’s mind. If you still aren’t sure about the $1.6 billion price tag, it may be because you are unacquainted with the whole viral Internet video phenomenon. I suggest a quick look at two of the all-time most popular Internet videos: The Llama Song video ( here) and the Badger Badger video ( here). If you are now completely mystified, then we are in agreement. Worst Headline Ever? You decide. Click here.

The Latest on “Going Private” Deals and D & O Risk

The D & O Diary has previously commented (most recently here) on the increasing risk of D & O claims arising from “going private” transactions in which incumbent management teams up with outside investors to buy out the interests of public shareholders. The most recent high-profile “going private” transaction to be announced – the Dolan family’s $7.9 billion proposal to take Cablevision private – has already resulted in a claim against the company’s board, according to this October 10, 2006 press release, here. Shareholders’ objection to the proposed transaction is that it allegedly puts the Dolan family in an advantaged position, to the detriment of public shareholders. A colorful expression of this concern is reflected in the remarks of a T. Rowe Price portfolio manager, who was quoted in an October 10, 2006 Wall Street Journal article about the Cablevision transaction ( here, subscription required), as saying that “I’m tired of management and private-equity firms trying to steal companies from underneath our noses, and I think this is another example of that.” An interesting commentary about the Cablevision transaction and the shareholder lawsuit appears on the Lies, Damn Lies blog, here. Shareholders concerns about “going private” transactions also extend to the ability of management to pursue potential buy-out opportunities in which management might participate, without even the board of directors' knowledge, in a way that potentially discourages or disadvantages potential competing bidders. A recent SEC filing of Kinder Morgan, whose shareholders are now considering a $14.8 billion buyout deal, provides an interesting perspective into this process. (The filing may be found here.) Kinder Morgan’s President entered discussions with investment banks in February 2006 about the possibility of pursuing alternative strategies. The discussion changed direction when the investment bank requested the opportunity to act as principal investor in a leveraged buyout. These discussions continued for months, yet the company’s board was not made aware of the potential transaction until May 13, 2006. According to the Wall Street Journal article ( here, subscription required) describing the Kinder Morgan transaction, The timing of events is notable because boards of directors often prefer to control the process of a management buyout as much as possible. The earlier they are aware of a potential buyout, the more they can shape the terms in ways that are favorable to the overall company….The tensions between management and board can become acute because the board is often interested in maximizing the number of bidders while management is eager for its own bid to succeed. For example, Mr. Kinder [Kinder Morgan’s founder], at the request of Goldman’s private-equity team, committed to not engage in talks with any third party in connection with any bid for 90 days. In an effort to keep the playing field more level, the board’s special committee…requested that Mr. Kinder terminate that agreement. The Kinder Morgan board' special committee later obtained more advantageous terms from the prospective acquirors and now the board supports the takeover proposal. The Kinder Morgan transaction has also resulted in a claim against the company’s management and its board of directors. (A copy of the complaint may be found here.) The attributes of a management-led buyout are fraught with potential conflicts of interest. Management is highly motivated to ensure that their proposed transaction will succeed, which may cause them to agree to structures (such as not to talk to potential competing bidders) that may favor their proposal, but to which shareholders might otherwise object. Nor are the potential conflicts of interest limited to management. The Kinder Morgan transaction reflects the unusual circumstance where the investment bank to who the company’s management turned for strategic advice emerged as the principal investor, putting the investment bank in the unusual position of advising the company' management in connection with the bank’s own proposal (in which management was participating) to buy the company. In circumstances packed with so many potential conflicts of interest, it is all too easy for allegations of wrongdoing to arise. The high stakes involved exacerbate this risk. For that reason, these transactions almost inevitably generate shareholder claims alleging that management breached their duty of loyalty and that the board breached their duty of care. A cynical view is that these lawsuits are nothing more than plaintiffs’ lawyers’ attempts to extract a toll from the transaction participants. But where management’s interests in a transaction potentially diverge from those of shareholders, the claims may present a more serious exposure. As the Journal article (linked above) discussing the Kinder Morgan transaction put it, "As private-equity transactions continue to sweep through the financial markets, investors will begin putting extra scrutiny on how these transactions come together, and how fair they are to all shareholders." Private Equity Conflicts: A different kind of conflict of interest may exist among the potential buyers in these “going private” transactions. According to an October 10, 2006 Wall Street Journal article entitled “Private-Equity Firms Face Anticompetitive Probe” ( here, subscription required), the U.S. Department of Justice is looking into whether some of the top tier private equity firms have developed a tacit understanding that they would not undercut each other’s takeover attempts with competing bids. Among other approaches under investigation is whether these firms form “clubs” drawing in potential competing bidders, which potentially could have the effect of depressing acquisition prices. The investigation apparently is in its early stages. A second article about the investigation appeared in the October 11, 2006 Journal ( here, registration required) Worse Than a Bad Hair Day: "Lightning Exits Woman's Bottom." (I am not making this up.) Read the story here.

SOX Whistleblower Protection: More Theoretical Than Real?